10 Questions with NIXON & ALI Screenwriter Chris Wilkinson

March 29th, 2005

INTERVIEW BY CHRIS WEHNER

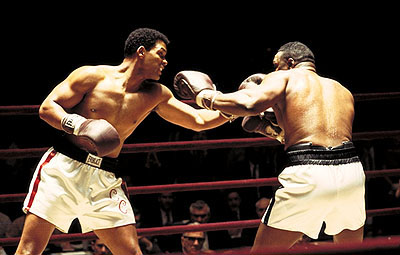

Continuing our "10 Questions..." series we feature an interview with Screenwriter Chris Wilkinson (�Nixon,� �Ali�), who stopped by our e-offices and was gracious enough to take time out of his busy schedule for a quick interview. Wilkinson contacted me regarding a review of his screenplay for the movie Ali I had written several years back. (He co-wrote it with his writing partner Stephen J. Rivele) A screenplay I enjoyed and thought would make an excellent film, only problem, director Michael Mann (�The Insider,� �Heat�) for whatever reason ended up filming something a little different. In all five screenwriters worked on the script, including Mann himself. Wilkinson was gracious enough to take time out of his busy schedule for a quick interview. He has been writing for a long time and has specialized in historically based stories. He has also shown diversity working as a director and producer. In this interview, Wilkinson discusses how he got into the business, what makes for good screenwriting, and much more.

Looking at your credits I'm surprised by the diversity: directing, writing, producing, ect. How did you get into the business?

I suppose, looking back, my credits are diverse. After film school at Temple University, I began making documentaries and industrials in Philadelphia. I don't think the film food chain gets too much lower. And my range of skills probably comes from the fact that I had so little money to make these productions. I would write, produce, direct, shoot, and edit them. Since, I began my career as a musician, I would sometimes even do the music.

During this time I also worked as a cameraman for ESPN. This was not the slick sports behemoth we know today. This was the ESPN that used to do midget chain-saw wrestling or celebrity shark-tagging -- virtually any sport they could fill 24 hours with (no matter how ridiculous). It was a lot of fun, actually.

A few of my documentaries won awards and appeared on PBS. This was

also a different PBS -- not just the "I'm waiting to Tivo Ken Burns'

next film" network. In the late 70s and early 80s, they did so many

cool shows and were open to showing all kinds of interesting stuff.

Perhaps they still are, but with our current slate of 7 billion

channels, I think it's been increasingly difficult for them.

A few of my documentaries won awards and appeared on PBS. This was

also a different PBS -- not just the "I'm waiting to Tivo Ken Burns'

next film" network. In the late 70s and early 80s, they did so many

cool shows and were open to showing all kinds of interesting stuff.

Perhaps they still are, but with our current slate of 7 billion

channels, I think it's been increasingly difficult for them.

One documentary I made about a ghetto firehouse -- "Engine 2, Ladder 3" -- was shown at a directing seminar I attended at the Maine Photographic Workshop which was conducted by Mark Rydell ("On Golden Pond", "The Rose"). Long story, short: Mark was impressed enough with my film, to offer me the job of Second Unit Director for his next film, "The River" which starred Mel Gibson and Sissy Spacek and was shot by --my then, and current hero-- Vilmos Zsigmond.

This was basically a miracle.

I worked with Mark on and off for the balance of the 80s, running his development company. "Nuts", "Children of a Lesser God", and "Man In The Moon" were produced. My duties required me to read between twenty and thirty scripts a week. And this was a real eye-opener -- people were actually being paid to write all this shit.

And I began to believe that I could be one of them.

That was when I hooked up with my writing partner, Stephen Rivele, who I vaguely knew through a mutual friend, we're all from Philadelphia. Stephen was primarily a novelist but also had been free-lancing as an investigative journalist. He was working on a piece that I thought had movie potential, so we decided to turn it into a screenplay.

Five years later, we sold the script to HandMade Films, George Harrison's film company. This led to a six-script committment -- and this was where we really got our chops together. It was like being a contract writer in the 30s, except instead of a studio story department, we were working for a completely unique production company that actually encouraged our stranger instincts. During this time, I did two more Second Unit/Producing jobs for Mark on "For The Boys" and "Intersection".

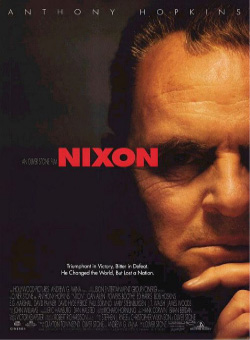

And then Stephen heard through someone in Oliver Stone's company that Oliver was interested in doing a film on Richard Nixon. I thought he was kidding . And as an avowed, life-long Nixon-hater, I was definitely not interested. But over the next few weeks, we became perversely fascinated with the idea.

And then... we thought of a way to tell the story. We faxed a three-page letter to Oliver and were hired to write the screenplay the next day. This, of course, never happens. "Nixon" became our first produced screenplay and was nominated for an Academy Award. Yes, another miracle.

After that we wrote "Ali" for Columbia and Will Smith and have several

scripts in various states of development -- among them "Houdini" for

director Ang Lee; "Sins of the Father for Jim Sheridan; "Kleopatra"

for Taylor Hackford; and "Copying Beethoven" which we are also

producing, Agnieszka Holland is directing, and which begins shooting

in Hungary in a few weeks.

After that we wrote "Ali" for Columbia and Will Smith and have several

scripts in various states of development -- among them "Houdini" for

director Ang Lee; "Sins of the Father for Jim Sheridan; "Kleopatra"

for Taylor Hackford; and "Copying Beethoven" which we are also

producing, Agnieszka Holland is directing, and which begins shooting

in Hungary in a few weeks.

You seem to specialize in period films and historical figures.

It's true, I am drawn to historical subjects. Part of it is a function of what you are actually offered. Part of it is the fact that I started out making documentaries, and have always been fascinated by real-life characters. And when you think about it, mythologizing these kind of characters has always been a staple of drama.

As someone who has written originals, adaptations, and rewrites, does it take any special adjustment to switch gears like that? How do you approach taking on something with a different source writer?

The process is pretty much the same. If we do a rewrite or an adaptation, it is because we were attracted to the original author's core idea. And, of course, you still have to do the research. However, we have learned to be a bit careful about the non-originals we take on because a great premise does not always lead to a great screenplay. And a brilliant book may be just that... a brilliant book.

Do you have any maxims as a writer, or guidelines, that you tend to follow when you approach a rewrite or adaptation, or even an original story?

Be true to your characters. As schizoid as this might sound, we try to let the characters tell us what they want to do, as opposed to forcing them into situations that will simply solve the story. We try to let the characters work things out for themselves organically.

Do you consider learning the art and craft of screenwriting as a continual process? Is it something that can be learned? Why?

I believe screenwriting is a very peculiar skill. You simply do not have the array of narrative tools that a novelist has. Perhaps this is why so many great, great writers have difficulty with this form and vice versa, of course. Screenplays are about events. If you have a ten page scene, someone better get laid or something better blow up. The inner life of your characters must be dramatized by events, by things happening. I sometimes think of screenwriting as more of a musical skill than a writing skill, because rhythm and timing are so important. But perhaps this is because I started as a musician.

And yes, I believe it is a continual learning process. I think it's very important not just to watch the movies of writers you admire, but to read their scripts.

You have a writing partner, Stephen J. Rivele, what is it about your writing relationship that makes your collaboration work? Is collaborating something you would suggest every writer try?

My writing partnership with Stephen Rivele works, I think, because he is essentially a novelist and I am essentially a filmmaker. And we have absolutely no ego about the writing process; we will go with whoever has the best idea, scene to scene and line by line. If we don't agree, we go with whoever can make the most compelling or passionate case for a character, story turn, whatever. If we still don't agree, we flip for it.

Stephen is also, quite simply, the smartest person I have ever met -- my wife, Cathy Guisewite, being the most talented.

How do you approach writing a story with a partner? Do you work together or sometimes divide up an outline and work alone?

We have worked the same way since the beginning. We do the research, then spend a few weeks discussing the characters. Sometimes, we work the story out quite specifically ("Nixon") and sometimes we just let it rock ("Copying Beethoven"). It depends. On a practical level, we write every word together, although sometimes one of us...usually Stephen will come in with a scene or a sequence of dialogue completely worked out.

What has been your most challenging project thus far and why?

Unquestionably "Kleopatra". Aside from Shaw and Shakespeare, this story has been filmed 17 times, 3 times famously, and once notoriously. Although it is not fair to judge Mankewiecz' film too harshly because what ended up on the screen was not really what he intended. The bottom line is that we felt, arrogantly perhaps, that it's an incredible story and it has never really worked on film.

We were hired to adapt two of Karen Essex' books, but, because of the vast amount of detail, we had to come up with a more focused approach. We felt strongly that every previous film has an error in common that we came to call the "Antony's girlfriend mistake". Simply stated, the story has never been told completely from Kleo's POV.

Normally, after the research is finished, we are very fast. We wrote the first draft of "Nixon" in six weeks and "Ali" in less than nine. After I returned from a lengthy trip to Egypt, we worked on the first draft of "Kleopatra" for more than six months. And this was an adaptation! Yes, it's true, "Kleopatra" was indeed a bitch.

I'm sure as a writer you are sensitive to other's work, especially when you are rewriting them, in terms of your own work, which has been rewritten, is it hard to see something you've worked on changed? Is it difficult distancing yourself from it emotionally?

I'm sure as a writer you are sensitive to other's work, especially when you are rewriting them, in terms of your own work, which has been rewritten, is it hard to see something you've worked on changed? Is it difficult distancing yourself from it emotionally?

Being rewritten is never fun. And if you write professionally in Hollywood, it will, in all likelihood, happen to you. It was so inspirational to see Paul Haggis' script for "Million Dollar Baby" remain untouched, just shot. But, that was Clint Eastwood, a truly brilliant and supremely confident director, who trusts not only himself, but the material that appeals to him.

I thought your draft of "Ali" was far superior to what ended up on screen. Why did Michael Mann take it in a different direction? What were the forces at work (as far as you're concerned) in its departure?

Thank you. I have no idea why Michael Mann made the choices he did. I will say that "Copying Beethoven" exists because of the frustration we experienced on "Ali". After that we resolved to write a film, and structure a situation in which we could control the destiny of our work. And, as I mentioned, we are also producing "Copying Beethoven", and it starts shooting in a few weeks.

"Nixon" was an excellent movie. What kind of research was involved with it and does it ever get to the point (in your research) where you feel to a degree that you know this character inside and out? When do you say, enough research! And start writing.

"Nixon" required a great deal of research indeed. We actually did an annotation that is included in the published version of the screenplay Although, that version was at a point where the script was in transition, and I think the final version is much better. If I remember correctly, we used over 70 sources. We did write the first draft very quickly, but we were ultimately on the project for nearly two years, and the research continued all through the writing.

There is a point where you reach critical mass on the research and you know you are ready to write. On "Nixon" there were times when I felt Stephen was actually channeling the Old Trickster. It was actually a little spooky. I took solace in the fact that I could channel Ron Ziegler.

What are you working on now, what does the future (hopefully) hold?

We have several things on the horizon. We just finished "Embedded" for Mike DeLuca and Columbia. It is based on Nicholas Kulish's book "Last One In", and is the story of a gossip columnist who, through a bizarre set of circumstances, ends up with the Marines at the tip of the spear of the Iraq invasion. We are also working on an HBO pilot based on my experiences as an ESPN cameraman and Stephen's as a staff photographer for the Philadelphia Eagles. After that, we will do a script which is called "Rivele/Wilkinson Untitled" because we are contractually not supposed to talk about it... Trust me, they have their reasons.

After that, who knows. We have a couple interesting offers that we are considering, and we may write another spec that we will produce, and I will direct. We'll see.

Continuing our "10 Questions..." series we feature an interview with Screenwriter Chris Wilkinson (�Nixon,� �Ali�), who stopped by our e-offices and was gracious enough to take time out of his busy schedule for a quick interview. Wilkinson contacted me regarding a review of his screenplay for the movie Ali I had written several years back. (He co-wrote it with his writing partner Stephen J. Rivele) A screenplay I enjoyed and thought would make an excellent film, only problem, director Michael Mann (�The Insider,� �Heat�) for whatever reason ended up filming something a little different. In all five screenwriters worked on the script, including Mann himself. Wilkinson was gracious enough to take time out of his busy schedule for a quick interview. He has been writing for a long time and has specialized in historically based stories. He has also shown diversity working as a director and producer. In this interview, Wilkinson discusses how he got into the business, what makes for good screenwriting, and much more.

Looking at your credits I'm surprised by the diversity: directing, writing, producing, ect. How did you get into the business?

I suppose, looking back, my credits are diverse. After film school at Temple University, I began making documentaries and industrials in Philadelphia. I don't think the film food chain gets too much lower. And my range of skills probably comes from the fact that I had so little money to make these productions. I would write, produce, direct, shoot, and edit them. Since, I began my career as a musician, I would sometimes even do the music.

During this time I also worked as a cameraman for ESPN. This was not the slick sports behemoth we know today. This was the ESPN that used to do midget chain-saw wrestling or celebrity shark-tagging -- virtually any sport they could fill 24 hours with (no matter how ridiculous). It was a lot of fun, actually.

A few of my documentaries won awards and appeared on PBS. This was

also a different PBS -- not just the "I'm waiting to Tivo Ken Burns'

next film" network. In the late 70s and early 80s, they did so many

cool shows and were open to showing all kinds of interesting stuff.

Perhaps they still are, but with our current slate of 7 billion

channels, I think it's been increasingly difficult for them.

A few of my documentaries won awards and appeared on PBS. This was

also a different PBS -- not just the "I'm waiting to Tivo Ken Burns'

next film" network. In the late 70s and early 80s, they did so many

cool shows and were open to showing all kinds of interesting stuff.

Perhaps they still are, but with our current slate of 7 billion

channels, I think it's been increasingly difficult for them.

One documentary I made about a ghetto firehouse -- "Engine 2, Ladder 3" -- was shown at a directing seminar I attended at the Maine Photographic Workshop which was conducted by Mark Rydell ("On Golden Pond", "The Rose"). Long story, short: Mark was impressed enough with my film, to offer me the job of Second Unit Director for his next film, "The River" which starred Mel Gibson and Sissy Spacek and was shot by --my then, and current hero-- Vilmos Zsigmond.

This was basically a miracle.

I worked with Mark on and off for the balance of the 80s, running his development company. "Nuts", "Children of a Lesser God", and "Man In The Moon" were produced. My duties required me to read between twenty and thirty scripts a week. And this was a real eye-opener -- people were actually being paid to write all this shit.

And I began to believe that I could be one of them.

That was when I hooked up with my writing partner, Stephen Rivele, who I vaguely knew through a mutual friend, we're all from Philadelphia. Stephen was primarily a novelist but also had been free-lancing as an investigative journalist. He was working on a piece that I thought had movie potential, so we decided to turn it into a screenplay.

Five years later, we sold the script to HandMade Films, George Harrison's film company. This led to a six-script committment -- and this was where we really got our chops together. It was like being a contract writer in the 30s, except instead of a studio story department, we were working for a completely unique production company that actually encouraged our stranger instincts. During this time, I did two more Second Unit/Producing jobs for Mark on "For The Boys" and "Intersection".

And then Stephen heard through someone in Oliver Stone's company that Oliver was interested in doing a film on Richard Nixon. I thought he was kidding . And as an avowed, life-long Nixon-hater, I was definitely not interested. But over the next few weeks, we became perversely fascinated with the idea.

And then... we thought of a way to tell the story. We faxed a three-page letter to Oliver and were hired to write the screenplay the next day. This, of course, never happens. "Nixon" became our first produced screenplay and was nominated for an Academy Award. Yes, another miracle.

After that we wrote "Ali" for Columbia and Will Smith and have several

scripts in various states of development -- among them "Houdini" for

director Ang Lee; "Sins of the Father for Jim Sheridan; "Kleopatra"

for Taylor Hackford; and "Copying Beethoven" which we are also

producing, Agnieszka Holland is directing, and which begins shooting

in Hungary in a few weeks.

After that we wrote "Ali" for Columbia and Will Smith and have several

scripts in various states of development -- among them "Houdini" for

director Ang Lee; "Sins of the Father for Jim Sheridan; "Kleopatra"

for Taylor Hackford; and "Copying Beethoven" which we are also

producing, Agnieszka Holland is directing, and which begins shooting

in Hungary in a few weeks.

You seem to specialize in period films and historical figures.

It's true, I am drawn to historical subjects. Part of it is a function of what you are actually offered. Part of it is the fact that I started out making documentaries, and have always been fascinated by real-life characters. And when you think about it, mythologizing these kind of characters has always been a staple of drama.

As someone who has written originals, adaptations, and rewrites, does it take any special adjustment to switch gears like that? How do you approach taking on something with a different source writer?

The process is pretty much the same. If we do a rewrite or an adaptation, it is because we were attracted to the original author's core idea. And, of course, you still have to do the research. However, we have learned to be a bit careful about the non-originals we take on because a great premise does not always lead to a great screenplay. And a brilliant book may be just that... a brilliant book.

Do you have any maxims as a writer, or guidelines, that you tend to follow when you approach a rewrite or adaptation, or even an original story?

Be true to your characters. As schizoid as this might sound, we try to let the characters tell us what they want to do, as opposed to forcing them into situations that will simply solve the story. We try to let the characters work things out for themselves organically.

Do you consider learning the art and craft of screenwriting as a continual process? Is it something that can be learned? Why?

I believe screenwriting is a very peculiar skill. You simply do not have the array of narrative tools that a novelist has. Perhaps this is why so many great, great writers have difficulty with this form and vice versa, of course. Screenplays are about events. If you have a ten page scene, someone better get laid or something better blow up. The inner life of your characters must be dramatized by events, by things happening. I sometimes think of screenwriting as more of a musical skill than a writing skill, because rhythm and timing are so important. But perhaps this is because I started as a musician.

And yes, I believe it is a continual learning process. I think it's very important not just to watch the movies of writers you admire, but to read their scripts.

You have a writing partner, Stephen J. Rivele, what is it about your writing relationship that makes your collaboration work? Is collaborating something you would suggest every writer try?

My writing partnership with Stephen Rivele works, I think, because he is essentially a novelist and I am essentially a filmmaker. And we have absolutely no ego about the writing process; we will go with whoever has the best idea, scene to scene and line by line. If we don't agree, we go with whoever can make the most compelling or passionate case for a character, story turn, whatever. If we still don't agree, we flip for it.

Stephen is also, quite simply, the smartest person I have ever met -- my wife, Cathy Guisewite, being the most talented.

How do you approach writing a story with a partner? Do you work together or sometimes divide up an outline and work alone?

We have worked the same way since the beginning. We do the research, then spend a few weeks discussing the characters. Sometimes, we work the story out quite specifically ("Nixon") and sometimes we just let it rock ("Copying Beethoven"). It depends. On a practical level, we write every word together, although sometimes one of us...usually Stephen will come in with a scene or a sequence of dialogue completely worked out.

What has been your most challenging project thus far and why?

Unquestionably "Kleopatra". Aside from Shaw and Shakespeare, this story has been filmed 17 times, 3 times famously, and once notoriously. Although it is not fair to judge Mankewiecz' film too harshly because what ended up on the screen was not really what he intended. The bottom line is that we felt, arrogantly perhaps, that it's an incredible story and it has never really worked on film.

We were hired to adapt two of Karen Essex' books, but, because of the vast amount of detail, we had to come up with a more focused approach. We felt strongly that every previous film has an error in common that we came to call the "Antony's girlfriend mistake". Simply stated, the story has never been told completely from Kleo's POV.

Normally, after the research is finished, we are very fast. We wrote the first draft of "Nixon" in six weeks and "Ali" in less than nine. After I returned from a lengthy trip to Egypt, we worked on the first draft of "Kleopatra" for more than six months. And this was an adaptation! Yes, it's true, "Kleopatra" was indeed a bitch.

I'm sure as a writer you are sensitive to other's work, especially when you are rewriting them, in terms of your own work, which has been rewritten, is it hard to see something you've worked on changed? Is it difficult distancing yourself from it emotionally?

I'm sure as a writer you are sensitive to other's work, especially when you are rewriting them, in terms of your own work, which has been rewritten, is it hard to see something you've worked on changed? Is it difficult distancing yourself from it emotionally?

Being rewritten is never fun. And if you write professionally in Hollywood, it will, in all likelihood, happen to you. It was so inspirational to see Paul Haggis' script for "Million Dollar Baby" remain untouched, just shot. But, that was Clint Eastwood, a truly brilliant and supremely confident director, who trusts not only himself, but the material that appeals to him.

I thought your draft of "Ali" was far superior to what ended up on screen. Why did Michael Mann take it in a different direction? What were the forces at work (as far as you're concerned) in its departure?

Thank you. I have no idea why Michael Mann made the choices he did. I will say that "Copying Beethoven" exists because of the frustration we experienced on "Ali". After that we resolved to write a film, and structure a situation in which we could control the destiny of our work. And, as I mentioned, we are also producing "Copying Beethoven", and it starts shooting in a few weeks.

"Nixon" was an excellent movie. What kind of research was involved with it and does it ever get to the point (in your research) where you feel to a degree that you know this character inside and out? When do you say, enough research! And start writing.

"Nixon" required a great deal of research indeed. We actually did an annotation that is included in the published version of the screenplay Although, that version was at a point where the script was in transition, and I think the final version is much better. If I remember correctly, we used over 70 sources. We did write the first draft very quickly, but we were ultimately on the project for nearly two years, and the research continued all through the writing.

There is a point where you reach critical mass on the research and you know you are ready to write. On "Nixon" there were times when I felt Stephen was actually channeling the Old Trickster. It was actually a little spooky. I took solace in the fact that I could channel Ron Ziegler.

What are you working on now, what does the future (hopefully) hold?

We have several things on the horizon. We just finished "Embedded" for Mike DeLuca and Columbia. It is based on Nicholas Kulish's book "Last One In", and is the story of a gossip columnist who, through a bizarre set of circumstances, ends up with the Marines at the tip of the spear of the Iraq invasion. We are also working on an HBO pilot based on my experiences as an ESPN cameraman and Stephen's as a staff photographer for the Philadelphia Eagles. After that, we will do a script which is called "Rivele/Wilkinson Untitled" because we are contractually not supposed to talk about it... Trust me, they have their reasons.

After that, who knows. We have a couple interesting offers that we are considering, and we may write another spec that we will produce, and I will direct. We'll see.

More recent articles in Interviews

Comments

Only logged-in members can comment. You can log in or join today for free!

Loading comments...

Loading comments...

Advertisement