John August Has BIG FISH

March 11th, 2004

John August Talks BIG FISH

by fred topel for Screenwriter's Monthly

(02/23/04)

John August burst onto the scene with his ambitious first film, Go. Telling multiple intersecting narratives, the Doug Liman-directed film launched August toward jobs including both Charlie’s Angels films, Titan A.E. and the unproduced How to Eat Fried Worms. His latest project is Big Fish for director Tim Burton.

Based on the Daniel Wallace novel, Big Fish tells the story of a son (Billy Crudup) trying to make sense of his father’s (Albert Finney) tall tales. With giants, Siamese twins and more, the son knows the stories are total fantasy and cannot understand why Dad won’t speak without hyperbole. Ultimately, he learns the emotional truth of the flights of fancy.

I caught August a bit sleep deprived. He’d been dealing with a water main break the night before but trucked through an interview despite a physical desire to crash.

What genre is this movie? Basically, it’s a drama. It’s a pretty funny drama, so if you want to call it like a family dramedy, that would be okay. The other description of it we sometimes use was a fable drama, which sort of gives you the sense that it’s not all serious. A lot is pretty whimsical and strange.

With myths and storytelling, is it also a fantasy? It is a fantasy story. I mean, there are really two story lines going on in the movie. The movie tells the story of Edward Bloom’s life the way he always told it, so about half the movie’s taking place in the real world, where Billy Crudup is playing the grown-up version of the son and Albert Finney is his father. They’re trying to come to terms with their relationship. The other half of the movie takes place the way Albert Finney claims his life always was from the moment he was born. So you’re constantly moving back and forth between this real world and the fantasy world which is clearly huge exaggerations of what could have possibly happened. It’s sort of a Norman Rockwell but more trippy and fantastical.

Is it like Go in that you’re telling multiple stories? It’s like Go except in that in Go the timeline was very rigid. Go only went back in time twice, where as this is constantly shifting back and forth between the real world and the recreations of these other times. The movie that’s probably closest to it is The Princess Bride, which, if you remember, is really told through Peter Falk to his grandson. The real world is a much more important part of this movie than it was in The Princess Bride and that’s probably the closest analogy people could come to. Again, Forrest Gump also moved back and forth a little bit.

Did you know Tim Burton would do this, or did he come on later? No, not at all. I read the book five years ago. I read it as a manuscript. It hadn’t come out yet, and I really liked it. The book is written by Daniel Wallace, who’s a southern novelist. This was his first book. He’d written short stories before that. I read it, really fell in love with it and recognized there was a way to make a movie and that that wasn’t very obvious but that I really felt I could do. At that point, I had only written Go. We had produced Go, but it hadn’t come out yet, and I was able to convince the studio that was releasing Go, Columbia, to take out an option on the rights for the book for me and let me adapt it into a movie. So at that point, there was no Tim Burton; there were no producers. It was just me and this book and my pitch on how the book could be turned into a movie.

Why wasn’t it obvious how to do it? The book has a lot of elements that are in the movie, but the book tells itself very differently. The present tense of the book isn’t a very important part of the story. It’s really just a collection of these stories that the father told about his life and clearly impossible things. His father’s best friend was a giant. It snowed 18 feet. The father’s born on the first day of rain after 20 years of draught. It’s sort of a Joseph Campbell-y kind of mythological exaggeration upon what a great life he lived and the adventures he had. And all those stories were fantastic, but they were enough to make a book, not enough to make a movie out of. When you read a book, you can put it aside for a bit, think about it and enjoy it for its own way, and you can reread stuff. The movie has to keep moving forward and really draw you through it, and I knew I’d have to find a different engine for the movie than the book.

What was that engine? That became almost a detective story, the son really trying to figure out who his father was. So the son who’s the narrator in the book isn’t really a character. He’s just the narrator. So it was a matter of inventing a life for him, inventing what their conflicts really were and finding a way to make that story and the investigation of that story compelling enough to base the movie on. So I knew if I could get the present-day stuff working well, cutting away to the fantasy funny stories would be rewarding. And it took a lot of convincing for the studio to see that that was really a valid approach.

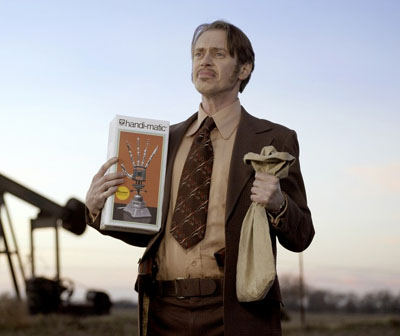

Did you create any myths not from the book? I actually ended up creating a lot of stuff that wasn’t in the book because chapters in the book are about four pages long and they’re a bunch of these tiny little stories. To do it in a movie, I needed to compress and combine, find new ways to get those things in there. So, there’s a big section in the movie that takes place at this circus and that doesn’t exist in the book. There’s a town of Spectre in the book, but it served a very different purpose than what I needed in the movie, so I ended up really changing it 180 degrees around. It was a very dark, depressing place and I made it this weirdly heaven-like, perfect place that he comes across too early in the story. And I took a lot of character names but had them do very different things. So the circus is run by Amos Calloway, who’s played by Danny DeVito. And there’s a character Amos Calloway in the book, but he does a completely different thing. It was also important to find ways to use the same characters throughout the story. So there are characters like Norther Winslow, who’s played by Steve Buscemi, who is mentioned in the book but doesn’t play a larger part in the story. So I needed to find ways he could keep coming back and being important. The same with the giant, who’s played by Matthew McGrory, who does a very important job when he first shows up on screen, but we wanted to be able to keep recalling him and letting him do stuff later on in the story.

What is the difference between a myth and a story? I think a story is anything that happens. So anything you can tell a person about what has happened is a story. A myth is a larger, symbolic story that’s told to illustrate a point or illustrate a truth. So the classic myths were (a lot of times designed) to explain natural phenomena or explain human emotions. Mythological gods, mythological characters are there to represent parts of ourselves or parts of our experiences and sort of an idealized version. What frustrates the Will character so much is that his father tells these stories that are clearly not even remotely possible, these idealized versions of how the father saw his life. So one of the major things I added to the story is that the Will character is a journalist. He works for United Press, so his job is to find the facts. So looking at the stories his father tells, there really are no facts, and it’s frustrating that his father maintains these things really happened when they couldn’t have possibly happened. So the story becomes about, if a person is telling lies, at what point is he really sort of telling the truth also.

Does the film answer that or is it ambiguous? The film does answer to a large degree what parts of the father’s stories are true. I think the most interesting turn of the movie is that the son keeps looking for a black and white answer and comes to recognize that the stories, while not factually true, have an emotional truth and a spiritual truth that supercedes the need to answer �How tall was the giant?� and �Were those twins really Siamese twins or were they just two women?�

Did you have any input from the author? I did. After I read the book and got Columbia to option the rights for me, I flew out and met with him. We actually met up at an IHOP in Virginia and talked for a few hours about the book and where stuff came from. He was able to fill me in on a lot of the backstory behind how he had found a lot of the stories. He’d done a lot of research on both the classic Homerian myths but also just southern stories. There are jokes that sometimes almost become like myths. The joke of the farmer’s daughter is almost myth at this point, and he’s done a lot of really good research on that. Honestly I don’t think he believed it would ever become a movie. He was flattered to have this attention to it, but he didn’t take it too seriously that it was ever going to become a movie because I was just this�the only thing I had done was Go, which hadn’t even come out yet, so it’s easy to see why he didn’t necessarily take me especially seriously although he was very respectful. So as I wrote it, there were no other producers. There was just the studio. So I sent him every draft, and he read every draft and came back with his thoughts. Then he became a much more active observer in the process than a novelist usually is.

Did he affect your writing? He offered some really good suggestions on things. More than anything, when a screenwriter is adapting a book, it’s almost like an adoption. It’s like a handoff where the novelist sees that his kid is being dressed up in these strange clothes that wouldn’t be his choice of clothes, but as long as he can see that the kid is being well taken care of, he’s happy enough to let things happen. And I think Daniel recognized that I needed to do some things a lot differently for the movie than he needed to do for the book, and I had some different goals for the movie than he had for the book.

What changes occurred when Tim Burton came on? Surprisingly little in a great way. I had done several drafts for Sony, and I took it to Dan Jinks and Bruce Cohen, who at that point had been nominated for American Beauty, and asked if they would produce it. They said yes, so I did two more drafts with them. By the time Tim came on, we really didn’t end up changing very much from the script as it stood. He shot that script. The stuff that did change along the way was based largely on his decisions, like we shot the whole movie in Alabama. Because of that, there were certain things that were written that were just too hard to find in Alabama. There’s a sequence that involved a small mountain or a big hill, and we would have basically had to build the hill. Where we were shooting was just too flat to do it. When we got our cast involved, like we cast Jessica Lange who plays Sandra, Albert Finney’s wife�she was a more prominent actress than we ever envisioned for it, so we ended up writing some extra material that supported her and Albert’s love story just because we thought there was an opportunity that we hadn’t really taken advantage of. Beyond that, there was very little that changed once Tim came on board. He seemed to really get it. I kept waiting for this big batch of notes that never came.

You were on the set? Yeah, I was down there for two and a half weeks during preproduction in Alabama, and that’s where we did the final pass to get everything the way we wanted to shoot it. You end up rewriting 60 pages, but you’re only changing one or two things on a page. So I was down there for that. We did the cast reading. It was a very long shoot, like five months, so I ended up coming back in the middle of it, not really to change stuff, just to see what was going on and to meet with some of the new actors who’d come in because you’re telling the story of a man’s entire life. You see him at very different ages, so there’s an infant, a young boy, Ewan McGregor and Albert Finney playing the same person. Jessica Lange’s character is played by Alison Lohman as a younger version. Helena Bonham-Carter plays three different ages in the story. So there were times where a new actor would come on, and I was there to help make sure that everything was working out okay. It’s always flattering to be thought of being invaluable on the set, but there really was nothing for me to do. During most of the production, I was actually up in Vancouver shooting a TV pilot for ABC.

Are you usually on the sets of your films? It really depends. On Go I was there for every frame shot. I directed second unit on Go and was crazy super involved. For Charlie’s Angels I wasn’t. I would only go if there was something they really needed me for. And this was sort of split. I was there to help get stuff running, but I didn’t stay involved on a daily basis. In terms of production, I think a writer is most crucial in those few weeks right around the very start of production when things are getting figured out. Then, a writer tends to be very helpful in editing, getting those last things to make sense and making sure the pieces of the story add up again.

Why were you there the whole time on Go? Go was my first film, and it was a really ambitious movie to be done on the short schedule we had. I was also co-producer on that movie, so even though I didn’t have to be around, I certainly wanted to be around for everything. All movies are hard to make, but Go was uniquely challenging in that the plot line of Go�you couldn’t drop out any scenes. Every scene depended on every other scene, so if one scene didn’t work, everything sort of fell apart. So I think also because Doug wore so many different hats in production because he’s his own director, he’s a cinematographer, he’s the cameraman, so there were things that I could help out with on the set that a director who wasn’t trying to do so much might not have needed.

How does your journalism background help your writing? Well, journalism and screenwriting are both sort of ruthlessly efficient. You’re trying to tell the most information with the least amount of words, and it’s a very highly structured writing where your goals are very specific. Journalism had this pyramid style where you should theoretically be able to cut off a story at any point and it should still sort of make sense. Journalism also has similar sort of style criteria where you don’t editorialize unnecessarily. You stick to certain rules. Screenwriting’s much the same way in that you’re trying to be as creative and expressive as possible in a very rigid format. You’re only allowed to say what a person could hear or see. You can’t talk about what a character is feeling or anything that can’t be visualized or communicated on screen. So I think the limitations and the frustrations of those two fields are pretty compatible as opposed to fiction, where you can do anything.

How does the film school path prepare a screenwriter? I went through a producer's program. I went through a two year producer's program at USC called Peter Stark. While I had some screenwriting there, the emphasis was really on physically producing movies. So I learned how to budget, how to schedule, how to break down a script. I learned how studios work, and I learned what the jobs were of all the people whose credits rolled on at the end of a movie. That was hugely helpful. I'm not convinced you can really teach somebody how to be a writer, but you can certainly teach them how things work. I learned a lot about how stuff worked through film school. I also had just zero understanding of the movie industry, so having two structured years of learning was a huge help for me and got me over a lot of my insecurities and a lot of my naivet.

What is your writing schedule? I'm in my office from nine to six, Monday through Friday. Some of that time I'm writing. A lot of that time I'm doing other stuff that's kind of job related or not job related. You're answering e-mails, doing all the other stuff you have to do to keep your life running. I don't have insanely great work habits. I don't have one of those things where I write from 10 to 11 every day and I generate these three pages or these six pages. I write as much as I need to write to complete whatever needs to get done. So different times I've had to write 20 pages in a day or keep up these tremendous values, and there have been times where I've slacked off for a week. My life ends up being a lot like college midterms, where you really buckle down when there's a paper due and you take it a little bit easier when there's not. I used to beat myself up a lot more for slacker habits, and I just realized it's the way I do things. I now have faith that stuff gets done when it needs to get done.

What drives your writing? Ultimately, it’s your characters who have to tell the story, but I think what gets me excited to sit down and actually work on one script rather than another script is generally the idea of it, the theme of it, what’s unique and unusual about it. So while I love great characters, I think a lot of times you can have great characters who are trapped in the wrong story, so you always want to find that blend of the most interesting, exciting story you can find and then figure out who are the best characters to be in that story. I do a lot of work for the Sundance Institute, which has this twice yearly filmmaker lab. So for two weeks a year, you sit down with these newer screenwriters, and you help them work on their projects and help them develop the best possible versions of their scripts before they go off and shoot them. What can be really frustrating is reading very talented writers who haven’t sort of gotten a firm grasp on what they’re doing. They have these really compelling characters and really interesting situations, but they haven’t figured out the best way to tell the story. More than anything right now, it’s the story that gets me going.

What advice would you give aspiring screenwriters? I’d say two different things. When you sit down and you read a script, it sort of doesn’t look that difficult. While the format is strange, it’s not that many words. It sort of feels like anybody can do it, and then once you do write a script and it’s like, �Wow, it’s properly formatted,� you feel like that’s such a huge accomplishment. �I’m now a screenwriter.� Recognize that the ability to write a scene that holds up is the very first step in actually being able to tell a movie story. A new screenwriter should read every good script they can possibly find. They should also read every bad script they can possibly find because I think one of the most valuable things to recognize is that just being able to put down your sluglines and your dialogue and have people say clever, witty things isn’t what actually makes a script good or makes a movie compelling. There’s some sort of essential quality that takes a long time to develop. And your first script, while it might have great things, will never be your best script. And there’s a lot of learning; there’s a lot more craft to it than you recognize at first.

What was your big break? My big break was a couple smaller breaks. My first script was what I just described in that it was pretty good. I thought it was terrific, but it was really just pretty good. But it got me started and got me my first writing job. I think Go was really my big break in that it was the first movie I’d written that showcased that I could do a lot of different kinds of things. Before that, the first two movies I’d done were kids movies; so I was just thought of as being a soft, kids writer. Go was helpful even before there was a movie. The script for Go was helpful because it showed that I could write funny, dangerous things which were much more compelling for most people who wanted to have me write their movies.

How many unproduced scripts do you have? There are sort of two categories I’ll say about my unproduced scripts. There are things that I’ve just written all by myself that have never gone anywhere, and there are four of those. That’s frustrating, but at the same time, they’re all mine, so at some point I could do something with them if I really wanted. What gets to be more frustrating is I have movies that I’ve worked on for other people or other studios that really aren’t mine but that I poured six months to a year of my life into, and those get frozen in development. You live every day with some of these characters and these scripts, and they’re never really finished because they never really become movies. So I have at least a dozen of those. In total, I’ve written I think like 25 screenplays.

How do you write action scenes for those movies? Do you leave it open for the choreographers? Writing action sequences is tough because you want to make it clear to the reader what’s happening and yet not be just exhausting. So you end up talking about the broadest dynamics of the fight, but you don’t go in and choreograph every punch. I tend to be pretty specific about what’s going to happen in terms of what the fight looks like and who the main players are. Knowing that, at least that gives a framework for how the choreography is going to run. You want to know who’s fighting whom, where they’re at and what the key interactions are between the different pieces of the fight. Of the original fight scenes that I wrote for the sequel, several of them are very close, and some of them are just completely new and different from what I had envisioned.

Do a lot of new writers make fatal mistakes with the wrong structure? I think a lot of times new writers worry a lot about the structure and not about sort of the movie they’re making. They forget their instincts as a person who’s seen a lot of movies and start to believe the dogma about when act breaks need to happen on such a page or else the whole story is going to fall apart. I really feel like the classic guru advice about this is that how a movie is structured is always drawn from two or three different movies that they’re hammering to fit into this pattern. I don’t think it’s really useful for most writers.

How far can a writer push format and structure without turning off readers? I think a writer can push it extraordinarily far if he or she is thinking like the reader. If the writer can take himself out of his own head and just be the person reading the script and be as interested and compelled and confused as that reader will be, I think you can write a script that doesn’t have any classic structural qualities and still maintain their attention. To me, am I turning pages in the script because I’m fascinated about what’s going to happen next? If I am, then something is working, and it may not have the classic structure, but it’s working, and there’s a lot to be said for that. Go doesn’t have anything approaching a classic structure, yet within each story, there’s a lot of tension. There’s a lot of drive, and you can understand both what the characters want and what the movie is trying to do.

Was Go influenced by Pulp Fiction? It was to the degree that I don’t think it could’ve been made whatsoever without Pulp Fiction . I wrote the first section of Go as a short film that a friend was supposed to direct. He never got time off from his job to direct it, so it just sat around for about a year. Then, when I had some free time, I went back and said, �Well, I actually could make this into a full length movie.� That 30 page short film is literally the first 30 minutes of Go. It’s the story of Ronna, Sarah Polley’s character, trying to make this very tiny ecstasy deal. All of the characters who drive the next two parts were set up in the first 30 page script, but there wasn’t anything for them to do in the rest of the short film, and I knew what the rest of their stories would be. Then, I also recognized very quickly that I couldn’t just cram their stories into that first section. The Ronna story relied on having that same internal tension, so I just had to restart the whole movie in order to tell those other two stories. At that point, Pulp Fiction had just come out, so at least it was perceived as being a valid way to do things. Pulp Fiction wasn’t the first movie to play with time that way. You have Jim Jarmusch’s Mystery Train. You have Rashomon. There were other precedents for doing it, but when it came time to make a movie and we had to describe what it was doing with time, thank God there was Pulp Fiction that you could point to and say, �Oh, Pulp Fiction, here’s a $100 million movie that did what we’re doing, so it’s not like people are going to be bewildered.�

Are you looking for films to direct? I’m writing stuff that I eventually may direct. I think I would only do it if I felt like I’d written something that needed to be done exactly one way, that I couldn’t really stand to see anybody else direct. A lot of people do use writing as a way to become directors; and it’s never been my thing. If I could just keep doing what I’m doing right now for the rest of my career, I’d consider myself very, very lucky. - FT

To read more you'll need to subscribe to Screenwriter's Monthly, a new print magazine delivered to your doorstep monthly. For more information

More recent articles in Interviews

Only logged-in members can comment. You can log in or join today for free!

No comments posted.

Advertisement