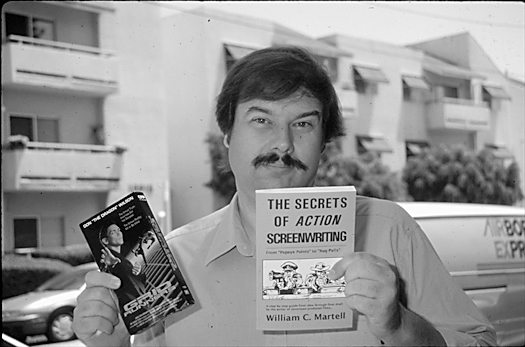

William C. Martell, Screenwriter of over 16 Films

March 11th, 2004

Interview with William C. Martell

Interview with William C. Martellby: Kenna McHugh

The Washington Post calls him "The Robert Towne of made for cable movies".

William C. Martell has written sixteen produced films, including "HARD EVIDENCE" which was "video pick of the week" in over two dozen newspapers, and beat the Julia Roberts film "Something To Talk About" in video rentals when both debuted the same week (Video Store Magazine Top 30 Chart). Mr.

Martell was the only non-nominated screenwriter mentioned on "Siskel & Ebert's If We Picked The Winners" Oscar show in 1997.

Martell screenwriting credits include "STEEL SHARKS" (1998, Cabin Fever); "HARD EVIDENCE" (1995, Warner Home Video); "INVISIBLE MOM" (1996, New Horizons); "BLACK THUNDER" (1998, Royal Oaks); "CRASH DIVE!" (1997, HBO WORLD PREMIERE MOVIE March 97) "TREACHEROUS" (1994, 20th Fox); "VIRTUAL COMBAT" (1995, HBO WORLD PREMIERE MOVIE); "NIGHT HUNTER" (1996, Orion/Moonstone); "VICTIM OF DESIRE" (1995, Orion/MGM); "CYBER ZONE" (1995, New Horizons); "THE BASE" (1998, HBO WORLD PREMIERE MOVIE)

When Martell isn't scripting he plays the other roles as a columnist

for Script Magazine, screenplay advisor for Roger Ebert's Movie

Answer Man column and contributor to Writers Digest Magazine. Above

all that, Martell has written a book, "The Secrets of Action Screenwriting."

Kenna McHugh met up with Martell in Northern California while he was conducting his first ever screenwriting workshop, which happened to be at the Sacramento Film Festival.

Send $14.95 + $2 Postage and Handling

($3 P/H for 3 day US Priority Mail)

($3 P/H for our friends in Canada)

($5 P/H for our friends in other countries)

(U.S. currency, check or money order)

William C. Martell 10915 Bluffside Dr. #104 Studio City, CA 91604

Kenna: Why did you write your book "The Secrets Of Action Screenwriting"?

Martell: Friends kept giving me their scripts to read because I'd had so many made. Often, I'd read the scripts and the same problems would pop up, so instead of typing the same notes over and over again, I typed up a little booklet. Now I could just hand this booklet to someone and say "Check out page seven, it gives a step-by-step on how to write a plot twist", or "Page nine has my trick for how to introduce your lead character". That way I could share my knowledge and experience without taking me away from writing scripts... which is how I make my living.

My friend Bill Jones thought I should turn it into a book and get it published. Now it's ten pages longer than Linda Seger's "How To Make A Good Script Great" and filled with all kinds of stuff; from pacing to the villain's plan to my "Sixteen Steps To Better Description". Though aimed at action writers, 90% of the information works no matter what genre you're writing in. It's one of the few books about screenwriting written by someone that actually makes a living writing scripts.

Kenna: What was it like working with the Navy and Department Of Defense on "Steel Sharks".

Martell: I had read an article in Variety about the Department Of Defense liason in Hollywood. The DOD will grant access to film with military equipment if your script is 100% technically accurate. This means they will let you film on aircraft carriers, film tanks on manuevers, etc. for the cost of fuel. The DOD co-operation was part of the pitch in "Steel Sharks". Producers love to get stuff for free, and my script could get them an aircraft carrier, a bunch of F-14 fighter planes, some submarines, a bunch of helicopters, and an entire Navy SEAL Team... for a few hundred dollars.

You know how cool it is to have Billy Dee Williams on the deck of an aircraft carrier with helicopters taking off behind him? They flew our crew out to a carrier doing maneuvers in the Pacific and let us shoot part of our movie on it! Though Gary Busey was on a set, the Navy gave us stock footage of a US 688 Attack Class nuclear submarine from their private library. Stuff used in commercials and training films. I had done a bunch of research before writing the script, had schematics of every deck of the submarine, floor plans of the aircraft carrier, and had my friend Bill Jones who used to be a Top Gun pilot answer some questions. Bill knew an ex-Navy SEAL, and I came up with a bunch of questions for him as well. Once I had the first draft of the script finished, we submitted it to the Navy. If the Navy rejects the script, they tell you why. But my script made it through. We got total cooperation, and I was given a tour of an aircraft carrier and a submarine to help me write subsequent drafts. I got to Q&A a sub crew, sit at the launch controls, and climb around inside. In the torpedo room I actually touched a nuclear missile. Weird. Once we had Navy/DOD approval, we could go along on SEAL team training exercises and film them jumping out of helicopters... absolutely free!

The film ended up having the look of a sixty million dollar action film, woven though we made it on a TV movie budget. Of course, the director 'de-characterized" all of the characters, making them flat, bland, and completely cliche... but that's another story!

Kenna: Briefly define an action scene.

Martell: When conflict becomes physical. It isn't emotional conflict, it isn't verbal conflict, it's people trying to hurt each other. Fist fights, shoot outs, car chases.

In a thriller, the protagonist is trying to avoid physical conflict... he or she is usually on the run like Cary Grant in "North By Northwest" or Harrison Ford in "The Fugitive", but action movies are about protagonists who turn and fight. Sometimes these protags even go LOOKING for conflict (like Rambo and all of those Ah-nuld Schwarzenegger characters). The first fiction film ever made, Edwin S. Porter's THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY, was an action film!

Kenna: What makes a good action sequence?

Martell: Reversals. Reversals are like a good news/bad news joke. A teeter-totter. "Just when you thought it was safe". They tug at the audience/reader's emotions. It's one cliffhanger after another, and the audience stays on the edge of their seats wondering what will happen next. In "The Fugitive" Agent Gerard is chasing Harrison Ford down the stairs. Ford reaches the lobby, but Gerard is right behind him. Ford breaks through a crowd of people, and sees the automatic exit door only a few feet away (good news). But the doors are whooshing closed (bad news). Gerard is right behind him (worse news). Ford squeezes through the doors (good news)... but his foot gets stuck! (bad news) Gerard draws his gun, and gets ready to shoot (worse news!). Ford tries to wiggle his foot out Gerard takes aim. Ford squeezes his foot out of the door (good news). Gerard fires! (bad news.) Ford hits the dirt (good news). Gerard re-aims (bad news). Ford stumbles to his feet (good news). Gerard has a PERFECT shot and squeezes the trigger (bad news). BANG! The glass scars... its bullet proof. Ford gets away. (good news) Using reversal to create an action scene makes for an exciting read. The goal is to get the reader to actually skip the dialogue to get to the next action sequence. Good news/bad news.

Kenna: How do action scenes play a role in telling a story?

Film is a VISUAL MEDIUM. Movies are about PEOPLE DOING THINGS. Often a character will say one thing but do another. What he/she does is what moves the story along. Actions speak louder than words. This is true regardless of genre.

In an action film, the action scenes ARE the story. They expose how a character reacts in conflict, how they solve or avoid conflict, how they feel about conflict. You should be able to watch any movie with the sound off and not only understand the story and plot, but understand the characters though their actions and reactions.

If conflict is the basis of story, than anything that shows conflict is telling the story. Let's go back to HARD EVIDENCE. Greg Harrison plays a boring businessman, completely out of control of his life. His partner walks all over him, his marriage is stale, he can sleep walk through his job. So he has an affair, hoping to add some excitement to his life... and gets too much excitement when he finds out his mistress is a drug courier.

In an early scene: Greg and his mistress meet a drug kingpin with a suitcase full of money. Greg has been manipulated into doing this and is afraid to back out. Fear controls him through out the scene. In a later scene: Greg and his wife meet the drug kingpin with a suitcase full of money. I echoed the earlier scene so that the audience could SEE how Greg's character has changed. Same situation, but this time Greg controls the scene. He has learned to be aggressive again. He is working WITH his wife, as a partner. His actions in this scene show us how much his character has changed over the course of the movie. The action scenes show us the character arc and tell us the story. Moving pictures are... Moving. Pictures. They are stories told in a visual medium (pictures) through actions (moving). In screenwriting, actions always speak louder than words.

Kenna: How is the role of pacing important in an action script?

Martell: Pacing is critical regardless of genre, yet it's usually an after-thought in most scripts. Too often no one realizes how slow their script is paced until someone gives them a story note to that effect. I think pacing needs to be built in to a script's structure. Producer Joel Silver ("Lethal Weapon", "Die Hard") says you have to have something exciting happen ever ten minutes. I think that holds true in comedies, too... just with something REALLY funny.

The idea is to keep the pacing brisk. I think part of our job, as screenwriters are to explode bladders. A customer buys a big Coke for $5 and about halfway through the film, they have to go to the bathroom. They are looking for that dead spot in the film so they can run to the bathroom. Our job is to keep them in their seats, no matter how painful it becomes. Make sure there ARE NO dead spots! Keep the script so exciting there isn't a spare minute to rush to the bathroom.

I have an outlining method called "Timelining" I explain in my book that focuses on pacing. If you outline your script so that something exciting happens every ten pages or so, you can keep your pacing tight... and explode a few bladders while you're at it.

Kenna: In HARD EVIDENCE how did you work with the director to pull off some of the action scenes?

Martell: I never met the director on HARD EVIDENCE! A Canadian production company made that film for a US distributor (Saban - those MIGHTY MORPHIN POWER RANGER guys who own the Fox Family Network). I dealt only with the distribs, then they shipped the script to Canada and made the film. But I did write the script the director filmed, so I did my job and he did his.

For example, there's a scene in an underground garage where Gregory Harrison fights and kills the giggling gunman Dietrich. That action scene runs about four and a half pages in the script, and clocks at 4:40 minutes in the film.

When Greg throws the money at his face and pulls out his gun - that was in the script. When Dietrich kicks the gun from Greg's hands - that was in the script. That whole fight is directly from the script: from Greg backing into the pillar, to Dietrich slamming his head into the car, to Greg kicking Dietrich and Dietrich grabbing his foot and flipping him. I wrote a bunch of fun fight gags in the script and the director filmed them. He did his job, I did mine. If it ain't on the page, it ain't on the stage.

Action scripts require action sequences made up of action gags. Because movies are about WHAT PEOPLE DO (as opposed to what they say or what they think) action sequences reveal character, advance plot, and can be used to explore theme.

I often 'echo' an action scene - write a scene in the opening with one result, then write a similar scene later in the script and show how the character has changed by having different actions produce a different result. HARD EVIDENCE is filled with scenes like this. In the underground garage scene, I even call attention to it in dialogue - in previous gunplay scenes, Greg was the one with the gun pointed at him, in this scene, he's pointing the gun... controlling the scene. This scene VISUALLY ILLUSTRATES his character arc.

Kenna: "Black Thunder" was released in September on video, how did you write it?

Martell: Typical assignment! The producer had signed a three-picture deal with "American Ninja" star Michael Dudikoff and called me in to pitch. He wanted to do a movie about helicopters or stealth fighter planes, so I came up with three stories for each, and pitched them the next day. They liked one of the Stealth stories, so they cut a check for me to write it.

That pitch was: "How do you find an invisible war plane.... Before it finds you?" Our new Nova Stealth Fighter, capable of bending light outside the human visual spectrum (totally invisible), is stolen by terrorists. Now we have to find it before the terrorists can use it as a first strike weapon.

I had to find out everything I could about Stealth fighter planes. I bought five books, including "Skunk Works" and "Stealth Fighter Pilot", and my Tom Clancy "Fighter Wing" book and my ex-Top Gun buddy Bill Jones' for lingo and flying information.

They gave me three weeks to write a first draft, so I really had to hustle. Based on script, poster and cast, they pre-sold most territories before we had shot a foot of film! The film was in profit before we began! The stealth fighter plane was stock footage the producer could buy. They sent me a stack of videotapes with stock footage I could use in the film. There was some great F-117A Stealth Fighter Plane dog fight footage, and some amazing Blackbird spy plane stuff. I used all of it in my script. Writing scenes that put our stars in the cockpits. Putting them in control of the planes.

I did two rewrites on the script. Though I fought for certain elements, the script was changed... and not for the better. But that's all part of the job. Once you sell the script, it's theirs. If they think it would be better with a singing-dancing-donkey in it, you have to write in the singing-dancing-donkey... or they fire you and someone else writes it in, only worse.

In the case of "Black Thunder" the pre-sales success was its downfall! Because the producers were in profit before we shot the film, they trimmed the budget. They'd already made their money, so they didn't care about the film. Instead of hiring a "character star" like Billy Dee Williams to play the General, they cast an inexpensive actor... then used footage of Frederic Forrest from another movie to get another name on the screen. Unfortunately, I had to write Forrest's "stock footage cameo" into the script. Yech! Hey, the check cleared and the film was made. MY SCRIPT is still great. It's sitting on my shelf. THEIR SCRIPT is the one on film.

Kenna: From you Hollywood Script interview, you stated you were not a union writer. How does a writer, with 17 films, stay non-union?

Martell: Easy. There are about 150 studio films made every year, and maybe another 50 (WGA) union Indie films. Compare that to the 500-700 non-union Indie films made every year. There are more non-union jobs than union jobs, so I just go where the work is. I'm not anti-union, I was a very active union member when I worked for Safeway grocery, even wrote some of the hand-out literature for the union when we were on strike. But the WGA has made no effort to organize these 500-700 films per year, so the minute I join the union I say adios to any of those 500-700 jobs. When I sell a big studio script, I'll join the WGA. Until that point, I'm going where the jobs are.

Kenna: What the heck is "Invisible Mom" doing on your resume?

Martell: Hey! That film's on ShowTime this week (10/98)! The Video Movie Guide gives it three stars. I actually slow danced with Dee Wallace Stone from "E.T." and "The Howling" at a party after she was cast as the lead.

Oh, yeah. What's it doing on my resume? After writing a bunch of thrillers and action films, I was afraid of being 'type cast'. I had heard that a producer friend of mine was looking for some family comedy scripts he could make cheap, so I went in and pitched. "Invisible Mom" sold on the title! (That's one of those things no one ever talks about - your title. It has to tell the audience what the film is about, PLUS get them excited about the film, all in a couple of words.)

"Invisible Mom" was actually a cut in pay to write the script, but I thought it would be fun, and add to my resume. Plus, it was a film my nieces could see. It ended up being #3 on the "Kid-Video" rental charts, and placed at Santa Clarita Film Festival.

Kenna: Give me an idea of your work schedule-"Day in the life of William C. Martell".

Martell: Sleep late! Actually, there are two work schedules: Spec scripts and assignments. If I'm writing a spec script (no boss, no deadlines) I try to write 5 pages a day, six days a week, and finish a final draft in a month.

A few months ago I began writing a weekly entertainment news column for Dean (ID4) Devlin's online magazine Eon, so now I only have 5 days a week to write scripts, and it's taking me about a month and a half for every first draft.

I have a lap top and a bicycle, so on nice days I'll pedal from one coffee shop to another, writing a couple of hours in each until I run through 6 hours of battery time. If I finish my 5 pages, I ride to the nearest Movie Theater and reward myself.

On assignments, it depends on the deadline. Earlier this year I had to write a script in 2 weeks that was good enough to attract top talent, a good enough to attract investor $. I didn't sleep much. That first draft signed a 2 time Oscar nominated actress, and was used by the distrib to pre-sell a bunch of territories so that the producer could get a bank loan.

People think I write fast, but actually I just write regularly. I don't allow myself excuses, and stay at the keyboard until the job is done. Some days it takes me more than 12 hours to write my 5 pages!

Kenna: How do you handle the infamous "writer's block"?

Martell: There are lots of different kinds of writer's block, and each one requires a different solution. If I wake up stupid (happens frequently) I may want to write, but just can't concentrate. I break the work into bite sized pieces. My 5 pages will probably be 2-3 scenes. So I break it down by scenes, then by pages, then by quarter pages (13 lines). I'll jot down what I need to accomplish in that quarter page, then organize it into a beginning-middle-end, then do the typing. It isn't fun, it isn't easy, but I can fight my way through 5 pages on a bad day... one line at a time.

Hey, sometimes life sucks. When I worked in a warehouse and life sucked, I could still do my 8-hour shift. But writing takes a certain amount of passion... I still use the above method, but I preface it by trying to get out of my depression. Sometimes I re-read an old script of mine, sometimes I'll watch something I wrote (usually this sinks me deeper into depression, though), and sometimes I'll just take a bike ride and forget about everything.

I think most writer's block is just not wanting to do the work. Heck, nobody really wants to work every day. But if writing is your job, you have to write. No excuses, no 'but I'm just not in the mood today'. Plumbers don't get 'plumber's block', right?

Kenna: Have you ever had doubts about your career?

Martell: Every day. So what? After writing a couple of low budget films made in Oakland, my career ended and I went to work in a warehouse for a decade. Ten years of manual labor. During that time I wrote three scripts a year. By the time I sold my first "Hollywood script" I had written about 44 scripts! The key is to actually like writing. Like the work. This business is tough, most scripts never get bought or made, so you have to enjoy the writing part. Writing has to be its own reward.

Kenna: Would you ever mentor a new writer?

I don't mentor individual writers, but...I'm a regular fixture on CompuServe's screenwriter's forum, and usually give notes and guidance whenever a new (or old) writer posts 10 pages. I also answer questions, often use my own scripts as examples. A writer I met on CompuServe, who bought the old Xeroxed version of my action book when it was about 80 pages, gave me a script to read for comments. I gave him a pile of notes, he rewrote the script, and sold it to Warner Bros!

I also write a nuts & bolts screenwriting column for Script Magazine, where I share everything I know about writing scripts. My column focuses on techniques. Most screenwriting books and seminars are by non-writers... outsiders looking in. They may not know HOW to write an action sequence, but they know that action sequences are important. I know HOW to write an action sequence because I do it for a living... so I can SHOW you how to write a reversal, or explain the 'minor mischief trick', or show you how to write a plot twist, or explain how suspense works... And I share techniques in every issue of Script and in my book as well. That way I can 'mentor' thousands of people at a time.

To find out more about William C. Martell's book, go to his web site: Click Here

Kenna is a highly regarded writer for The Screenwriters Utopia

. She has also worked for StoryCrafting: The Fiction

Writers Magazine.Kenna is a bright young screenwriter with

a great future. Thanks Kenna!.

See Kenna's Home

Page, on Planet Utopia.

Kenna is a highly regarded writer for The Screenwriters Utopia

. She has also worked for StoryCrafting: The Fiction

Writers Magazine.Kenna is a bright young screenwriter with

a great future. Thanks Kenna!.

See Kenna's Home

Page, on Planet Utopia.

More recent articles in Interviews

Only logged-in members can comment. You can log in or join today for free!

No comments posted.

Advertisement