Jeff Vintar was Hardwired for I,ROBOT

August 17th, 2004

Jeff Vintar lived a life not ideal but still somewhat enviable for most screenwriters. He sold several specs but waited through years of development to see most of them still unproduced. But he kept working. He did rewrites on high profile projects like Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within; one of his specs was produced in Germany, and his most recent became this summer’s blockbuster I, Robot.

Now, I, Robot is supposedly based on an Isaac Asimov book, so how could this spec script have the same basis? Well, since it’s the story of a robot suspected of murder, it actually fit well into the canon of Asimov’s collection of robot stories.

Scheduled for a 20-minute slot but ending up talking for 90, Vintar revealed halfway through that he never realized how much time he spent alone. “I’m usually sitting in this room with the ringer on my phone turned off, writing, not really seeing anyone, not speaking really to anyone. Then, when the prospect of actually speaking to someone comes up, it’s shocking because you’re actually going to talk to somebody for a change. Then, when you get started, you have a tendency not to stop.”

How did your own original spec become an Isaac Asimov adaptation?

I, Robot started out as a spec script of mine called Hardwired, which I wrote 10 years ago. It was one of my first spec scripts. I was living in San Antonio, Texas, and I didn’t have an agent. I sold the script in 1995 to Walt Disney Pictures, Touchstone or Hollywood. The original script was very much the same story that has made it to the screen. It was about a detective named Del Spooner who is called to the site of a murder by a hologram of the dead man. He finds himself involved in a mystery where all the suspects are robots, cyborgs, computers, holograms. He’s really the only human being in the story. Now, the original script was very much like an Agatha Christie type of mystery. It took place in one setting, one floor in one high tech building. Other than that, it follows the same line as the finished film. A while [after buying the script, Disney] attached a good director, Bryan Singer. I worked on the script with him. The problem was that the script was so contained — almost like a stage play — that we had to find a way to make this work for the studio. So we transferred the setting and put it on a space station as a way to explain the fact that it was so confined. I did a few drafts there.

Now, at Disney, the project eventually descended into development hell. The last draft I saw there a few years later was basically like a monster movie. The detective was replaced by a group of marines, and instead of the robots, they were going to the space station to destroy the monster. It had been developed in a completely different direction, which was a very heartbreaking thing for me. For a few years, it was dead, and then around 1999 Fox was interested in doing a robot film. They were looking at picking up Hardwired, so they did. They brought me in and asked me to do a new rewrite from my original spec. So that process began, and I went out to Australia for a month to work with Alex [Proyas] and a good development exec he had at the time. We worked on a treatment in the spring of 2000 to take my original stage-play-like mystery and open it into a big budget studio film. This ended up being far simpler than anyone really thought. Basically, we took the most important beats — the discovery of the robot, the interrogation of the robot, the discovery of a second hologram of the dead man — we took those major beats, and we just opened it up so that the setting was a metropolitan city. It was surprisingly easy, and it worked well.

Then Fox threw another surprise at us. They had finally acquired the rights to Isaac Asmiov’s short story collection I Robot. So the problem was presented to us; can we make this film the first movie in a series of I Robot films. Can we make Hardwired [into] I Robot. So that was the next step for us.

What elements of Asimov did you bring in?

The irony of the whole thing is that, through Hardwired, I actually got a number of offers through the years. But these offers always fell through because the parties could never finalize the rights. Several times through the years I had been approached by people with the idea of getting the rights to I, Robot, and asking me if I was interested. Of course, I always said that I would. Now, the reason it’s a good fit is because Hardwired is essentially a classic murder mystery. It’s a locked-room mystery. A man is killed in a locked room; nobody was inside but machines, so how could he have been murdered? In that way, it’s a very classic, old-fashioned murder mystery at its core. And Isaac Asimov was doing the very same thing. The I, Robot short stories are a series of little, tiny mysteries. He creates the three laws of robotics; he presents them to us in every story, and then he gives us a mystery. A robot has done something wrong. A robot has gone missing. A robot is disobeying orders. How can it happen? And by the end of the story the puzzle is put together. So you can see how what Asimov is doing is not that far removed from a classic murder mystery. How was the murder done? How could the three laws have been broken? How could a robot kill?

When we started this process, the feeling was of course that it would be very difficult to get a movie out of the I, Robot stories. They’re a very loose collection of stories. The idea was that Hardwired would make a good introduction to the Asimov world. So all we really did was change the name of my female lead. She was named Flynn. We called her Susan Calvin [after] the female lead in the Isaac Asimov stories. Of course in those stories, she’s an 80-year-old woman. We of course are keeping her the 30-year-old woman, very close to the character she was in the original spec. So we thought of this story all the time as a prequel. Alex has called it a prequel quite a number of times. We took the female lead and called her Susan Calvin. This required that we rewrite her much more intellectually. Susan Calvin is a robo-psychologist, the first one. The female lead in my original script was a member of security, actually. So she was much tougher. Consequently, the detective became less intellectual and more of a traditional cop. We of course changed the name of the company to U.S. Robotics and inserted the three laws of robotics. That is really it.

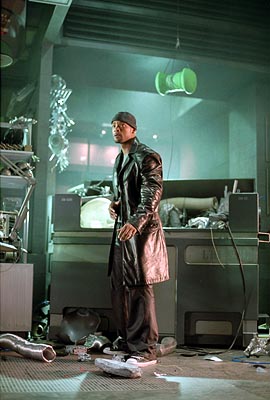

There is a scene in the film where the robot suspect does go off and attempt to hide from the police. Of course, like a robot would hide, he goes to the robot plant and hides among thousands of robots that are identical. It’s a great way for a robot to hide. This was inspired by a story in Asimov’s collection called “Little Lost Robot,” where a man tells a robot to go get lost, but he says it in such a way that the robot takes it literally and hides among the other robots, so Susan Calvin has to find a way to figure out which is the lost robot.

What did Akiva Goldsman do on the project?

Akiva came on when Will Smith came on the project. Through the years, the problem has always been the same problem you get with these big genre films, which is the expense. You’ve got to create a world of robots, so it’s going to be an expensive film. There’s always that tension between the growing nature of the film, the number of robots in the film and the intellectualism of the film. Asimov’s work is very talky and Hardwired to a large degree was the same way. Even though it took place in the sci-fi setting, it was very much a classic murder mystery with a lot of talking. The tension is always that there’s too much talking and here we need more action. This was going to be an expensive film. As the script progressed, it was a process of very carefully — without losing the essence of the mystery — trying to whittle that material down and create as much entertainment as we could.

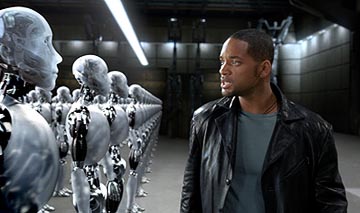

At some point, Will Smith became interested, and that was great for the project because it was a way, obviously, to justify the growing expense. He was great for the role. Akiva came on to do the Will Smith rewrites, meaning that he took the film even further in the direction of a Will Smith event film.

Your script didn’t have much action?

Well, there was action, but not to the extent that there is in the final film. I’ll give you an example: the scene that I mentioned earlier about the fugitive robot hiding among the other robots. When I wrote that in the script, I think Sonny, the robot, was hiding among 50 robots. This scene was always a point of contention. Can we afford this scene? Should this scene be in the film? I think in the finished screenplay, there are actually 1,000 robots in that scene. So after struggling and fighting for that scene for quite a number of years, when Will Smith came on, the robot count went up from 50 to 1,000. That was the Will Smith effect. That took the film to a higher level. So Akiva came in and really opened it up further, really created a sense that we’re not just solving this murder mystery and we’re not just saving this city. We’re saving the world, so the script takes place on a larger scale.

How did it feel to collaborate with an Oscar winning screenwriter?

It was good. I like the finished film. I mean, the finished shooting script. I haven’t seen the cut of course. But I like the shooting script.

Did you work together, or did he just do his draft?

He did his thing. We didn’t really bounce ideas off each other. I think as difficult as these things can go it was a good collaboration. He got the script and really without changing the essence of it, was able to make it more of an action film.

How many lines did Will Smith ad lib?

I think he actually stayed fairly close to the script. I think people will be surprised. From what I’ve seen, the dailies I’ve seen, he’s giving a really intense, dark performance.

What’s your writing schedule?

I usually get up about six, especially now that I have a daughter. So I get up about six, start working and usually work until about 11 or 12. Then I take a break, have lunch with my daughter, play with her a little bit in the afternoon. She goes down to her nap, and then I get back to work revising. And when she gets up, I usually try to spend a little more time with her and then, back in the evening, revise again. So I guess there’s three periods: early morning, afternoon and evening. If I can come out of the day with three pages that are fairly close, then I’m very happy. It doesn’t always happen that way. Sometimes you end up with two. Sometimes you can get lucky and write five. But I try to keep myself to that schedule.

Do you worry about overwriting when you’re trying to perfect those three pages?

There is a certain point when you have to get away from it, but to me, writing is really rewriting. That’s not a secret.

But you’re rewriting before you move on. Most people mean that to say they rewrite after finishing a draft.

Oh, for me, no scene is ever written in one shot. I usually write it several times to get it to the point where I would consider it a first draft. So, yeah, I do a lot of rewriting as I go. I don’t think your first draft of a scene is what it can be. You’d have to rewrite it several times, work on it, craft it until you really discover what that scene is or really work that scene for everything that you can. My first draft is not a first draft exactly. It’s a first draft that’s been rewritten to a certain extent.

How did you get your agent?

It took me a long time to find an agent. I was doing what everyone does: getting the agency list from the Writer’s Guild and sending out letters. It was very difficult to get anyone interested. The only thing I had going for me a little bit was I had just come out of the writer’s workshop at the University of Iowa, and some people seemed to sort of recognize that program and thought, “Yeah, OK, send me the script.” I wasn’t having any luck, and finally, I found an agent in Utah. She was my first agent, and it’s very bizarre to have an agent in Utah, but my reasoning was, “Well, I’m not in Los Angeles. Maybe I can get an agent outside of Los Angeles to take me on,” and she did. She met with an agent in L.A., and they started getting my scripts noticed. At the time, I had about five spec scripts. In late 1994, I had moved to San Francisco with my wife. We were down to $600 in the bank, and I was actually considering going back to the Midwest and teaching English. Then in December of 1994, I optioned Long Hello and Short Goodbye for about $6,000. That’s what kept me afloat in San Francisco.

What drives your writing process — character, story or theme?

I really think that it’s a combination of the three. Also, structure is the thing that is probably the unifying principle. My scripts tend to be, as some people tell me, strong on structure. But I think what is most exciting about writing is that there is so much possibility inherent in the structure and in narrative that is rich and fascinating. To me, it’s the way that these things combine — the characterization, the theme, the structure of the piece, the way you can manipulate these elements to find new ways to reveal character, new ways to embellish a theme with a fresh structure and drama, the interrelationship between these things. That makes screenwriting so much fun.

What are you working on now?

I had a meeting recently, and I’m going to work on a comic book adaptation next. It’s an adaptation of Y: The Last Man, a wonderful comic book written by a really talented writer named Brian Vaughan. It’s about one man. A plague wipes out the entire male population except for one seemingly normal young man and his pet monkey. And the mystery of the story is, of course, what happened to all the men, and why did this guy survive?

Is it easier to do an obscure comic than a well-known Marvel property?

There are a lot of things that come into play. Of course, when you’re working on a property, my experience was that there you’re coming into a situation where there are a lot of opinions. Studios can have lots of opinions. The comic book companies are going to have a lot of opinions and a lot of requirements. You’re going to have your own opinions, and sometimes these things clash. I, Robot wasn’t really a problem of adaptation because we were really just taking a pre-existing story and tweaking it to fit into the Asimov world. Right now, I’m in the last few days of finishing an adaptation of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy. Now this is an entirely different situation. When you’re doing I, Robot, you’ve just got a series of short stories. You can theoretically assemble an original narrative and call it I, Robot and still have respect or integrity toward the source material. With Foundation, you can’t do that. Foundation is more coherent. It’s still a collection of stories, but they’re more closely related. It’s more of a true narrative, and if you’re going to adapt Foundation, you’re going to have to be very loyal to the source material. In this regard, it’s very difficult because Foundation is still made up of a series of stories that were originally published separately in the pulps during the 1940s in “Astounding Science Fiction” and so forth. And of course you have the fan base, which is there right from the beginning. Whether it’s true or not, they’re very vocal, and they have a lot of say in what goes on.

Did you get that job off I, Robot?

Yeah, they said, “Hey, we’re stuck with this. Do you want to do it?” Anyone who really reads the Foundation trilogy would probably say, “Let that one go; don’t try it.” But I wanted to try it because it is Fox, and I have a good relationship with them. Also, the producer is Vince Gerardis at Created By. He’s been working on this for quite a while, and I thought I would have a lot of support on this one. You need support on something like Foundation. You need a good creative producer, and you need a good atmosphere at the studio. Thanks to Vince’s passion for the project, the atmosphere at the studio, and now thanks to I, Robot, I think that Foundation has a fighting chance.

Will it be one film or a series?

Right now, we’re planning it as two films. The first film will be called Foundation, and the second will be called Second Foundation. In the original trilogy of books, when the stories were collected into novel form, the books were called Foundation, Foundation and Empire and Second Foundation.

What happens to the third element?

So much of the Foundation stories take place over the course of, I think, 500 years that we’re narrowing down our story to the latter half of the period. We’re having to excise a lot of the early material, so we’re using part of the first novel, Foundation. We’re using a great deal of the second novel, Foundation and Empire, and then the second film will use a great deal of material from the third book, Second Foundation.

Who will direct?

There is a director attached, a really wonderful guy named Shekhar Kapur. Very smart. We’ve been exchanging e-mails and phone calls between here and England, here and India. It’s been a nice working relationship so far.

Who is Y for?

Y: The Last Man is for New Line Cinema, and Benderspink is the producing company. Benderspink has a lot of good guys, and David Goyer is producing.

Did he have any comic book advice for you?

No, actually, he’s been great. Somebody asked me, “Is it going to be hard to have a producer who’s a writer?” I didn’t have an answer. It never happened to me before. David has been terrific.

Will that be based on a specific set of comic book issues?

Actually, this is going to be a very faithful adaptation of the comic. If you look at the comic, I think anyone who reads it will see that it seems in some ways readymade for film. It’s intelligently written with a provocative approach to what could be a goofy thing. You could take the idea of the last man on earth, and you could make an extraordinarily silly film. But The Last Man works because, as the story progresses, you believe every detail. It reads as a genuine piece of speculative science fiction. I’m actually being very faithful to it. The problems with adaptations are the same ones that you always have in any kind of apocalyptic film, something like a zombie film or horror film. You’ve got a great opening. Everyone turns into zombies; everyone dies. You’ve got a great road movie struggle for survival. The problem always is what happens at the end. How do you tie it up? How do you conclude the piece? That’s where I think in this regard my job as the adapter comes.

When is that due?

In about two months. So as soon as I finish Foundation, I’m skipping right over to that and starting Last Man, which is a funny thing, too.

Do they have a director or star?

No, not yet.

What other characters are there if it’s the last man?

Well, the women are still alive. It’s only the men that have died. It’s one man in a world of women, and of course this is why I say you could take this concept and make something extremely cheesy. But what Brian has managed to do in his comic is really create something that feels very realistic in the details. For example in issue three, York is going through Washington D.C. with Agent 355, a female government agent who is there to protect him. York hears something, and we find out that the women have created a monument to all the men they’ve lost. They’ve created a shrine. Of course, York says, “Well, where’s the shrine?” And 355 says, “Where do you think?” You see the Washington Monument rising very phallic-like up in the sky. Of course it’s a detail that is really extraordinary because the Washington Monument is like a big phallic symbol. It’s funny, but it seems genuine and true. Sure enough, all the women have created a shrine at the Washington monument, and they’re all there talking about the men they’ve lost. It just becomes a wonderful setting for a scene. It’s funny; it’s ironic; it’s touching, and it all sort of just comes together to create.

Does any of your work remain in Iron Man?

I wouldn’t think so because at the time, 20th Century Fox had X-Men, Fantastic Four, Iron Man and Daredevil. Even when I took that project, there was a sense of — I hate to say fatality, but I got the idea that this was the last try. That didn’t bother me because I met Stan Lee. My script is still retained by Fox even though the project has moved on to New Line.

Why are you so drawn to sci-fi?

I loved it as a kid, and I actually started out writing comedy scripts. Years ago, I used to draw cartoons and comic strips, and I never really had a whole lot of success. I had some things published in small local papers, but I used to write these comic strips. Then I moved on to writing short stories. That’s a tough business. I had a teacher [at the University of Iowa] — there were 17 people in the workshop class, and she told us, “Look, three years from now there’s only probably going to be two or three of you still writing.” Everybody of course was outraged, like you are when you’re a young student. “No, that’s not true. We’re all going to be writing.” She goes, “Look, only a few of you will be writing because the rest of you will have to move on with your lives. You’ll have to get a job; you’ll get married; you’ll have a kid. You’ll just have to carry on with the business of life, being alive. But those of you who do not, those of you who stick with it will eventually succeed.” This was coming from a woman who was in her sixties and had attained success as a novelist finally in her fifties, so she was a testament to sticking in there.

How did you get into sci-fi?

So she told us you’re going to have about 100 story rejections, and then you’ll sell one. I remember at the time thinking, “What kind of an arbitrary number is that?” I made it to 88 story rejections, and finally, I thought, “I’m going to try something else.” It just occurred to me — I have no idea why it didn’t occur to me earlier — that I loved movies. Why not try a screenplay? I did, and I loved the form. Then when you get into the screenplay business, you hear other arbitrary things like, “It’ll take you six years to see the finished film after you sell a script.” Of course, I’m working on 10 now with most of these specs. I started writing comedy scripts because I’d just come off doing these cartoons. I think they were pretty lame, not the greatest comedy. It was only when I finally tried a sci-fi script that things clicked for me. I think it was a couple of things. Love of the genre, of course. You have to know it and like it and want to play in that area. Science fiction, especially for a spec writer, offers you the ability to really craft a screenplay that stands out or that has something to offer because you can use the science fiction conventions to manipulate structure or to reveal structure and theme and character in a different way.

Final Fantasy was criticized for script problems. What is your take on that?

Final Fantasy was an interesting process. I wanted to write a remake of The Lady From Shanghai. Before I started that, they wanted me to work on a rewrite of Final Fantasy, a project the studio was going to make. It was a property that Sony owned, the video game franchise. It was in production, and it was a very ambitious project. They wanted to create the first photorealistic human characters, but they had script problems. They’d been working on a script for quite a long time, a year, I believe, maybe a year-and-a-half, almost two years. They sent it to me and said, “Can you look at this?” So I did. They wanted me to do two weeks of work on it, and I said, “I can’t do it because you really need a lot of work on this. You need six months of work.” They subsequently offered me three weeks and a lot of money, so I went, “OK, I’ll try it.” I did a three week rewrite, went out to Honolulu and met the mostly Japanese crew that was making the film. The story was by Hironobu Sakaguchi, who had created the game, and we worked together closely to try to give the story more shape and focus, create a true main character, which was Aki, and give the studio more of a sense of mystery and thrust. In the original stories, we knew right away that the aliens were ghosts, but in the final film, you learn this as the story proceeds. We gave the story a little bit of a mystery revealed through Aki’s dream, and it strengthened her character. In fact, the people who do like the film usually cite the dreams and the strength of the Aki character. I think the final film suffers from this strange phenomenon that the dialogue sounds like it was translated from another language, and it’s very frustrating to watch the film for that reason. The dialogue is very stilted.

What would you have done if you’d had six months?

It’s difficult because the story is very rooted in the anime tradition, so you’ve got your third act with the giant monster that rises out of the ground very Akira-like. At the end of the day, it is what it is. It was Sakaguchi’s story. I don’t really know exactly how to answer your question.

What was the University of Iowa’s Writer Workshop like, besides that teacher?

It was good. It’s a hard place to get into. I was lucky to get in. You have to be able to put a sentence together, but there are certainly many people who can put a sentence together and craft one short story or two. I found out years later that what actually got me in the program was one of my stories about a cartoonist. In the story, I drew some cartoons in there. This actually made my application standout and got me in the project. The program itself is like a lot of writing programs. You’re going to get out of it what you bring into it. There are workshops where you write stories, discuss them with your fellow writers and so forth. I loved being there because it enabled me to live two more years where I was devoted simply to learning to write. And of course, the only way to learn to write is by writing and writing again and again and again. It was time well spent. Programs like that are emotional places. People get frustrated sometimes because maybe they want more direction or they want more practical advice. If you go to a writing program and you’re just intent on using the time to write, you may find it a very rewarding experience.

What’s been the most frustrating project to come close to production and not make it?

It’s been very frustrating. It’s been great, too. When you’re just starting out, writing a 14-page short story can seem monumental and then again when someone tells you to write a 20-page one and so on. I remember thinking, “How can I write an entire screenplay?” But you do it and you get through these things. I recall a time when I never thought I would sell a screenplay. Then you sell one, and you have these expectations. Of course, I think this career is a constant series of adjusting your expectations. I was lucky enough to sell or option three screenplays in 1995, Hardwired, Long Hello and Short Goodbye and Spaceless. Now let’s look at what’s happened to all three of these. Hardwired went into development hell at Disney and was dead for many years, out of my hands. Now it’s a Will Smith film. Who could have predicted that? I can’t even express the highs and lows that went along with that last 10 years. There were moments of complete agony, moments of tears, moments of surprise and happiness.

More recent articles in Interviews

Only logged-in members can comment. You can log in or join today for free!

Advertisement