Still Old School: A Talk with CELLULAR Scribe Larry Cohen

September 28th, 2004

(Interview first appeared in September issue of Screenwriter's Monthly)

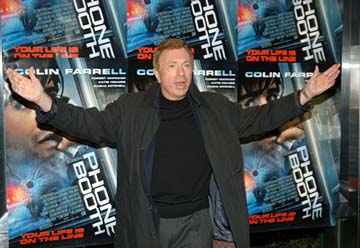

Larry Cohen started his career in New York writing television for NBC. He created the 1960s sci-fi show The Invaders. Cohen then moved into Hollywood production, writing scripts for such films as Return of the Magnificent Seven (1966) and Daddy's Gone A-Hunting (1969). The writer soon was writing and directing low-budget blaxploitation flicks Black Caesar and Hell Up in Harlem (both 1973), and cheap exploitation horror films.

As a B filmmaker, Cohen then turned out what is still considered a classic, It's Alive (1974), a ghastly but undeniably effective yarn about a killer baby (with music by Bernard Herrmann). Never slick or expensive, Cohen's films always maintained interest by falling back on the bizarre or unexpected.

In the 1990s Cohen was unable to generate the kind of budgets he needed to go beyond his B movie label, so he focused on his screenwriting and sought to get Hollywood’s attention the only way he knew how — with his writing.

At the age of 64, Cohen became an A-List screenwriter by reinventing himself from a B movie and exploitation filmmaker into a high concept screenwriter who has done more than anyone in recent memory to conjure up Hitchcockian premises. Films such as Phone Booth and the just released Cellular are constructed with setups that Hitchcock would have loved.

When Cohen ran into Steven Spielberg at the Oscars recently, the famed director told Cohen, “If Hitchcock were alive he would have wanted to direct Phone Booth.”

Cohen most recently sold his spec script thriller Captivity, his fifth thriller spec in the last five years. Phone Booth (2002) was sold in December 1998 for mid-six figures. Cast of Characters for $350,000 and Cellular (2004) for $750,000 were both sold in 1999. Man Alive was sold in August 2002 for mid-six figures.

In this exclusive interview Cohen discusses how he beat ageism in Hollywood, what makes for good suspense, what’s wrong with Hollywood movies today and how he has been able to be old school and still succeed.

How did you come up with the concept for Cellular?

After I wrote Phone Booth I wanted to do something else in the same genre. Everyone has a cellular phone now. In their cars, at restaurants — it’s on epidemic proportions really. I don’t carry one, but everyone else does. It’s something intrinsic in our lifestyle today as a society, so I thought maybe I could turn it into an element of a suspense movie that would be the antithesis of Phone Booth, where someone was trapped inside a phone booth for the whole movie. In Cellular the protagonist is able to maneuver through the city, constantly in motion, can’t stop moving and driven by the ticking clock. His battery is not going to last for very long. It’s life and death; the kidnapped woman in an undisclosed location needs his help. He can’t hang up or disconnect. It’s a continual race against time and connectivity. Very rarely does anyone have a long cell phone call that doesn’t have interference or disconnection. So I thought this is great suspense. That was the basic jumping off point.

In Daddy's Gone A-Hunting (1969) you had some extensive sequences where the kidnapper harasses the victim. Now it’s phone booths and cell phones.

Yeah, I’m sure I’ve used the phone a lot. It’s such a big part of our lifestyle.

Your reliance on phones as narrative devices on your last two pictures struck me as interesting. Why do phone’s bug you so much?

[Laughs] I don’t have a cell phone. But I did it that way because I wanted to do a double feature. I have a third one called Message Deleted, which is a thriller centered on an answering machine.

What in your opinion makes for good suspense?

The first key element is audience identification with the protagonist. You immediately identify and relate to the character. You want the audience to project themselves in the character so they feel the same emotional responses. That’s essential. Second, a unique twist, something that is somewhat unique as nothing is ever truly original. With Phone Booth, they did something similar in radio some fifty years before called “Sorry Wrong Number” with Agnes Moorehead, probably the most famous radio show ever done as far as dramatic programs go, written by Lucille Fletcher, who was the wife of my dear friend Bernard Herrmann the composer, who wrote the score for my film It’s Alive. That was the premiere show of its kind, constantly repeated on radio, in which a woman confined to her bed hears a murder being planned on a crossed line. As the show continues she realizes she’s the intended victim. It was made into a film [1948] starring Barbara Stanwyck. I always wanted to do a telephone thriller. Now I’ve done two.

How do you approach writing a suspense thriller?

I think you have to have the audience see everything through the eyes of one main character. You have to be careful to focus the audience’s point of view through that character, and once you capture the audience they’ll be in a better position to identify with the character. The problem with a lot of movies today is that you can predict what’s going to happen. You see the setups and know the payoffs. It’s always by the book. A lot of young writers and directors seem to copy what’s been done before or what’s been taught in a class. The setups and payoffs are so very clear anyone can guess what’s going to happen next. There’s no suspense with most movies today, no time taken to build up anything. Today, movies are just one big explosion or CGI effect after another. They just keep throwing on more and more production value. No buildup and no suspense — that’s the problem. Time has to be taken to build up the suspense.

If you look at a picture like North By Northwest, the famous crop dusting scene everyone talks about. Well, it starts way before that. There’s this big buildup to that chase through the cornfield. Cary Grant gets off the bus and waits. Cars go by; a bus goes by; people go by. Hitchcock really takes his time building up the suspense. You would never see that patience today with most filmmakers. The crop dusting plane just tops off the scene. You’ve got to give your audience time to get into the scene. Today, you’d have the guy get off the bus, and immediately, the plane would show up and chase him into the field. They’d probably have dozens of special effects shots, and the sequence wouldn’t play nearly as well emotionally with an audience.

Do you think that if Hitchcock had the technology available today he would have changed how he shot that scene in some dramatic way?

He would have still developed it the same way because he understood how to develop suspense. His payoffs I’m sure would have been technically much better because he would have wanted to use that technology. He was a very technically inclined director. He would have a better shot of the plane crashing into the gas truck, I’m sure. But that’s the final payoff of the scene, and the fun is what happens before that, the buildup. He would have maintained the same pace to the scene. I have no doubt. Special effects today are so big the audience isn’t even impressed by them, and they continually have to find ways to outdo themselves. After a while the audience is really numb to it. Instead of better it’s just bigger and lauded. I don’t mean to be old fashioned about it. [laughs]

No, actually, I completely agree with you.

I know a lot special effects movies do really well. Everybody needs to follow what they think is effective. But there are also a lot of special effects movies that don’t do really well. You’ve got to have characters with personality, and you’ve got to have a story.

Since his passing, some writers and directors have tried to emulate Hitchcock. You’re one who really does seem to pull it off.

I don’t think about what anyone else is doing. I think about what I’m doing and what kind of movies I want to see.

Cellular sold to Centropolis.

Devlin and Emmerich [founders] split and went their separate ways right about that time as well. Devlin took the project with him and took it to New Line.

Unlike Phone Booth, Cellular was extensively rewritten. Why did they take it in a different direction?

There are some changes, yes. Most of the suspense in the story is still mine. The protagonist of the story, the leading man, Ryan — they changed him from an adult to basically a kid. It’s more of a teen picture now. Both he and his girlfriend are young and talk about completely different things. I didn’t write any of that stuff. Once the phone call comes in, it’s still my stuff.

Your original screenplay had some twists that are now gone.

Yes, the original script had him do all this stuff, and partially it was a scam to manipulate him. It was a nice twist, but that’s a different picture. I think the people who see the movie will know what elements are mine. The other writer, Chris Morgan, is a very nice young man and was on set every day doing rewrites, which is something I’d never do. He deserves credit, and he did a nice job. It’s not the picture I intended, but I think it’s still a good picture. It holds together well, and what I contributed to it provides the glue that holds the story together. The fun of these things is the twist though, taking the audience down this road and then taking the thing in another direction. Like with Phone Booth, people wondered how long you can keep that guy in the booth. Well, you have to keep coming up with new twists to keep it interesting.

If you could give a young, up-and-coming screenwriter some advice or some words of wisdom, what would you tell them?

I’d tell them to keep writing. Like anything else, if you want to do it, do it all the time. Keep moving on to the next script regardless of what does or doesn’t happen with the last one. Sometimes it takes years to sell.

What’s a screenwriter’s job?

I think the screenwriter’s job is originality, at least striving for it. I don’t care to see remakes like The Manchurian Candidate. I don’t understand why the studios have to be so void of imagination that we have to start reaching back to these pictures we’ve made before, sometimes brilliantly like The Manchurian Candidate. You can’t duplicate that. A couple of years ago they remade Charade. How can you do that? There’s no reason for that. How can you do better than Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn? What’s the point of that? There are plenty of new writers out there with terrific scripts. Instead of seeking the scripts out, they’re constantly looking around to see what they can remake, make the quick buck.

No one wants to take a risk on an unproven writer, not even the directors. It’s a private party, and no one else is invited.

And then they’ll put one writer after another on a script. No matter how good the script is, they’ll put someone on it to polish it, and then the actors come along and have their own screenwriters; then the director brings in his ace writer. The result is usually a good script turned bad. Someone finds a script and gets everyone excited about it. They buy the script. They put into development. Then the downward spiral begins, and a few months later it’s not such a great script anymore. They’ve only read it about 42 times, so they get the bright idea of improving it and hire another writer. The script keeps getting changed, and pretty soon nobody knows why the hell they bought it in the first place, and the project is put into turnaround. I always liken a script to a piece of fruit. You bring it home; it’s juicy and delicious, and everyone is happy with it. Then it sits there on the table for a few days, and there are a couple spots on it. Pretty soon it’s ugly and mushy. No one wants it.

That’s a product of the corporate studio system today.

Sure, used to be you dealt with only three people. Not it’s 30. Too many executives with no understanding of what it takes to tell a good story.

Any plans to direct again?

Sure, I’d love to. I haven’t directed a picture in over five years. Writing is great too, and it’s my first love. I’ve had to do low budget movies because I want complete control.

You’ve got Captivity, which is in pre-production.

We’re trying to cast it.

What about your It’s Alive remake?

My 1972 film was number one at the box office. Because of the changes in gene development and cloning, I thought It’s Alive could be updated very easily. It seemed like a remake worth doing, so I got the rights back from Warner Bros. We’re going make that picture very soon.

What else are you doing?

I’m writing a screenplay for Warner Bros. called Bad Deeds.

You’re proof that ageism in Hollywood is not as active as some think.

There’s nothing that ever stops anyone from getting a job. I don’t believe in that ageism stuff. Nobody cares. If the script is good people will want to make the picture. If older writers want to sit around and bemoan not getting assignments, that’s their problem, I guess. There’s nothing stopping any writer from writing a spec script and putting it out on the market. I’ve written spec scripts all along. Nobody cares how old you are. It’s self-serving to a lot of people to blame their age for why they’re not working. I won’t do that. They’re not working because they’ve got nothing to say anymore with their writing. It’s OK to get old; it’s OK to get tired of the system, and it’s OK to quit, but don’t blame everybody else.

More recent articles in Interviews

Only logged-in members can comment. You can log in or join today for free!

Advertisement