INTERVIEW ARCHIVE: David Ayer Talks TRAINING DAY and DARK BLUE

This interview originally appeared in Screenwriter's Monthly Magazine in April 2003

December 14th, 2014

by Fred Topel

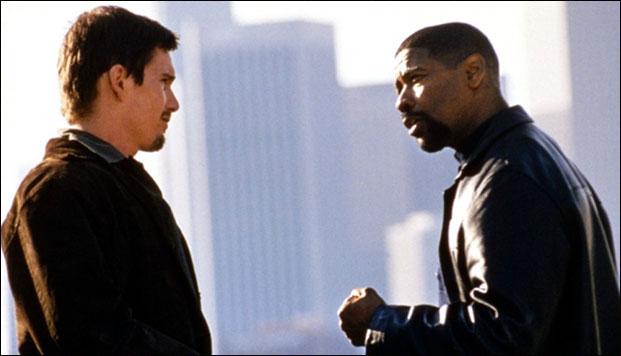

David Ayer looks more like the guy his characters would arrest than the guy who wrote about the characters. With a shaved head and goatee, he fits the gangster stereotype. Talking to him, though, reveals a man of ambition and intellect. After a successful script doctoring career and after writing the script that gave Denzel Washington his Oscar for Training Day, Ayer took on another sort of corrupt cop story, Dark Blue.

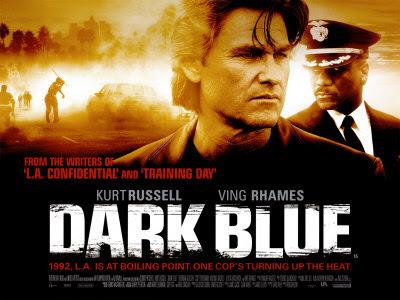

Set against the backdrop of the 1992 L.A. riots, Dark Blue tells the story of Eldon Perry (Kurt Russell). Perry is a third generation police officer, practicing law enforcement his own way until he realizes the end might not justify the means. As he contemplates the ramifications of his tactics of planting weapons and shooting false suspects, it may be too late to do the right thing.

Ayer was an electrician when he started writing scripts. He didn’t have any Hollywood connections, just a passion and the patience to see it through. He inherited the Dark Blue script from James Ellroy and made it his own. Find out what he thinks about corrupt cops and about the system of breaking into Hollywood.

Are you the corrupt cop guy now? I’ve definitely been writing in the law enforcement zone for awhile now. I’m going to be the whatever-they-pay-me-to-write guy.

How did it work out that you did two high-profile corruption stories? Well, Training Day, I wrote that in ‘95. That was kind of like my calling card script. Then, based on that, I started getting other rewrite jobs. And Alphaville [production company for Dark Blue], I guess they weren’t thinking very well at the time, they actually hired me. I was like nobody and really didn’t have much experience rewriting. So, they took a big gamble on me. This was ’96, so this project’s been a while, been around a long time. I was proud to do it. I was lucky to get the job and glad it worked out.

Did you work with Ellroy? No. It’s based on James Ellroy’s first screenplay. I guess it was originally about the 1965 riots and then he had done some work to update it and converge all this to the ’92 riots. Hopefully, we won’t have to update it ever again for new riots. He wanted to work on other projects and he had taken the script as far as he could. And, you know, screenwriting is like the Pony Express. If a horse gets tired, you grab a fresh horse and keep going. So, it’s whatever it takes to get the movie done.

Did you have free reign in adapting it? He had the basic story there, but it felt very novelistic. It was very dense, lots of storylines and my task was to narrow it down and make it more of a movie and pick the stories to focus on. Now, as far as execution, yeah, I made some major changes in the story. I consolidated characters. I changed Holland’s assistant from a male to a female. She became Michael Michele’s character. I made Bobby Keough, Scott Speedman’s character, younger. It had been skewed to a 40-plus man and I felt that a guy at that age would know the ropes already and wouldn’t be as susceptible to Eldon Perry’s magic.

Why make Holland’s assistant a woman? Efficiency of combining two characters. Ving Rhames’ character had had an affair in the past so I thought [to make it his assistant.] My mantra in writing is to make everything personal and to make it so claustrophobic and bring it in, make the circle of friends as small as possible. It was just screenwriting efficiency you could say. I kind of think of her as the only sane person in the movie because if you look at it, everybody else has the spin going on and their own personal issues and whatever. But she’s kind of the voice of reason to a great degree and people revolve around her and lean on her, which I think is interesting. I always like that one character that’s not messed up in a movie.

Did you write with Kurt Russell in mind? When I came on board, I was really working closely with Caldecot Chubb, the producer on this. And he had told me that Kurt was interested in this project. Jim Jacks, the other producer, is a good friend of Kurt Russell’s and was kind of like, “Hey, buddy, do the movie.” So, I never had any other actor in mind other than Kurt for the part. Normally, I try not to let thinking of an actor prejudice the role I’m writing and let the character be himself without being informed in that manner. But, I mean, I wrote this for Kurt. I saw him in the role. I think it was Kurt and I was ecstatic when the deal finally closed and he finally decided to do it. And then he knocked it out of the park and he’s great. It’s sick.

Was Eldon Perry less sympathetic in Ellroy’s version? The original script was a lot rougher. Again, the scope was a lot bigger, but there were things that I didn’t think you could quite pull off in a movie that you can get away with in a novel. Because a movie’s a visual medium and you see it, things can be a little stronger than they are just on the page. So, there were things I pulled back. And Eldon Perry is a very harsh, misogynistic, racist, brutal character and he was even more so.

Were you in LA during the Rodney King beating? Yeah, I was here. I was living in L.A. and it just seemed like business-as usual. The difference was that it got videotaped.

What do you mean “business as usual”? Well, I grew up in South Central. I lived there and LAPD operated in a certain manner at that time period. I’m talking about the ‘80s and early ‘90s. Those were the tactics they used. That was how they took down people who were not cooperative when they didn’t want to blast them. They could have blown Rodney King out of his boots. This was pre-bean bag and obviously two tazers didn’t work on him. Yes, a line was crossed. That’s not clean law enforcement you can say.

What is your relationship with the LAPD? I try and stay out of their jails as much as possible, but aside from that, the bottom line is this is a movie. This is fiction. It’s loosely based on real events and it’s an opportunity to tell a story and L.A. is a great arena. I think I write about the L.A. beat because A) I’m from L.A., and B) I think it’s just more interesting than the traditional Sidney Lumet-esque kind of borough police corruption we normally see.

Do you feel the LAPD is fair game? I’m not coming after them with a shot gun. I’m not attacking the department or anything like that. I mean, I’ve met some amazing cops. I’ve met some heartbreakingly dedicated cops. I’ve just seen what the wrong kind of culture in a police department can do. Now, having said that, they’ve totally changed that culture. They’ve changed the makeup of their patrol force. I mean, they’ve gone to really great lengths. They’ve opened up to civilian oversight. So, this movie’s a period piece in essence, almost a historical piece. I mean, look at the giant cell phones.

How did you write the riot scenes? I watched the riots. I sat on the Hollywood Hills and watched the city burn. I think at one point I counted 29 structure fires and you couldn’t hear one siren. Then, I knew people who were on the streets. I read a lot of stories. I talked to people. I did the research. Kind of by osmosis, but people running around breaking stuff is people running around breaking stuff.

Were the riots ever a bigger part of the script? They were always a backdrop and this isn’t the gestalt of the L.A. riots movie. This movie isn’t about the L.A. riots. The riots are a backdrop. They’re a ticking clock. They’re a metaphor for the end result of what Eldon Perry’s style of policing gets you. But I never try to get too deep into what that’s all about. It is self-explanatory from the movie. There’s definitely a lot of stuff addressed there.

Strip club scenes and cop movies seem to go hand-inhand. Oh, it’s mandatory. You gotta have a strip club scene. If your shoe leather trail isn’t taking you to a dancer, something’s wrong with your case. I had a thrill writing that.

Why wasn’t Holland (Ving Rhames) a bigger character? He was. He had a really big scene in the beginning, but a movie has its own tyranny of pace. You’ve got to get into the story and you’ve got to get the story cracking and I tried to develop Holland as much as possible. I actually wrote him as a much larger, much more involved, much more politically rounded character. So, it was a little heartbreaking to see some of his scenes go, but the focus of the story is Kurt Russell. You’ve got to service your principals.

What scenes got cut? There was a scene of Arthur Holland being courted by Cleveland police commissioners. We kind of start to see Arthur Holland setting up his plans earlier and it makes him a little bit more formidable to see that he is a force to be reckoned with early on. But again, in the name of getting the story kicked off, you had to make hard choices.

Why was it important to redeem Perry in the end? Your other corruption movie doesn’t redeem the corrupt cop. Because the reason I was attracted to this project was I think it said that a man like Eldon Perry, someone so almost genetically predisposed to his attitudes and mentality, can change, can see the truth. If the scales can fall from that guy’s eyes and he can change and have an honest transformation, then there’s hope for all of us. That was the power of the message that I saw and that’s why I did the movie. I mean, Training Day was more about the street level and was really a character study. I see this as almost a system study. The nuts and bolts of police corruption, the nuts and bolts of secret policing. The LAPD’s networks are notorious for intelligence files on criminal personalities. I don’t know if they still actively seek that kind of intelligence out, but they have incredibly sophisticated intelligence on it. So, you wonder what has happened to all that information and what has it been used for? I mean, it’s an incredible amount of power and no civilians can ever unlock those cabinets. So, it’s something that they guard very closely. They are just ruminations on how such a system can operate.

Does the end justify the means? Well, there’s the infamous question they propose ethics students and that’s if your wife is sick and you don’t have the money for the medicine, is it okay to go to the drug store and steal the medicine? I say yeah, absolutely. I’m not gonna let my old lady die. Having said that, policing is a different matter because you’re talking about other people’s lives and affecting other people’s lives. This country hasn’t cracked the code of law enforcement yet, and it’s up against an astoundingly formidable enemy in the form of organized crime and gangs. If the rules aren’t getting the job done, then we have to change the rules. That’s the way I see it. Law enforcement needs a choice to get the criminal organizations out of the community which makes life bad for everybody. If they’re breaking the rules, then let’s change the rules or let’s look at the tactics or let’s modify something.

How did you get into screenwriting from being an electrician? I was working construction after I got out of the service and I went to wire up a screenwriter’s house and told him sea stories. He thought I had something to say and talked me into writing a script. And I went and wrote my first script. To think someone of that caliber in the industry was interested in me, you gotta do it. To not take a chance would be a big mistake. I thought my first script would sell for a million and I’d never have to write again. I was really, really wrong.

Could you believe how big Training Day became? No. That was a shocker. I wrote that script on spec out of frustration. I was trying to make sales writing mediocre scripts, I guess, trying to anticipate what the studios would buy, and I wrote that for myself. I was tired of second guessing the system and I just wanted to say something.

Could you believe how big Training Day became? No. That was a shocker. I wrote that script on spec out of frustration. I was trying to make sales writing mediocre scripts, I guess, trying to anticipate what the studios would buy, and I wrote that for myself. I was tired of second guessing the system and I just wanted to say something.

What’s it like to see Denzel give that performance and win an award? It was outstanding. I was happy to help him get there. It was a great feeling.

How was your original script for Training Day different from the final film? Vast amounts of it, amazingly, made it through the development process unscathed. There was more of an action ending that had to be added on so you could sell the movie to the theater owners, because they know what sells tickets. Action sells tickets. So, I had to graft on the action module.

How did your script end? Just very simply with Ethan Hawke’s character, Jake, just dumping the money on the bed and walking away. I think we knew at that point that that was it. But that was the art movie version. That would have been a version no one saw. When you’re going full freight on a studio project, come on, it’s commercial speech. It’s for the profit, not show art, so we’ve got to be realistic.

What advice would you have for screenwriters trying to get their scripts read? No good story is going to remain untold. That’s axiomatic. If the script’s good enough, it’ll get made.

How do you get it to people? I think it’s less a matter of access and more a matter of having quality material, because there’s no conspiracy in Hollywood to exclude writers. There’s no walls. It’s not there. Hollywood casts a very wide net in search of good material.

How do you get an agent then? Write a great script. Spend thousands of hours learning how to write, re-write your script until it’s great. Quit listening to your friends because they’re probably not telling you the truth. “Yeah, it’s good.” Just learn the craft. Have some life experience. Have a voice. Have something to say. Don’t regurgitate other movies.

So what are people who have trouble getting an agent doing wrong? They need to spend 2000 more hours writing and learning how to write scripts. I’m totally convinced of that. I learned how to write by writing and writing and writing, having bad jobs and going home and writing and on weekends writing. Incessant writing. That’s how you learn to write. There’s no way around it. There’s no shortcuts. You can’t go to the right cocktail party and sell a script. That doesn’t happen. The material speaks for itself. The material sells itself.

What are you writing now? I’m producing, moving into directing and I’m doing production rewrites right now for Warner Brothers. I don’t know if I can say what project. I can say it’s an Ethan Hawke-Angelina Jolie movie. No law enforcement.

You’re still script-doctoring? Script fixing, yeah. I did Fast and the Furious, SWAT, some other stuff, U-571. I have a knack for being able to tear down scripts and build them back up.

Do you enjoy that? Yeah. It’s its own kind of reward, solving a problem. The cool thing about it is you get to go in, you get to save the day, everyone’s happy and you walk away before the real problems start. So, it’s real get in, get out. It can be a good life. It’s tough work though, very difficult, and the pressure’s astounding on an $80 million movie. People are screaming down your neck and it gets pretty intense.

More recent articles in Interviews

Only logged-in members can comment. You can log in or join today for free!

Advertisement